Just beyond Dealey Plaza, past the acrid smell beneath the Triple Underpass, lies Martyrs Park, a half-acre pocket of grass and weeds awash with the squeals of metal train wheels on Union Pacific tracks and the thrum of traffic on I-35. Scholars and activists in 1991 had to prod the city’s park department to give this tiny slice of green its proper name to memorialize a brutal event that occurred more than a century ago. Three Black men were murdered nearby, lynched in the Trinity River bottoms after being falsely blamed for a downtown fire in 1860 that the White business class interpreted as an attempt to trigger a revolt by enslaved persons.

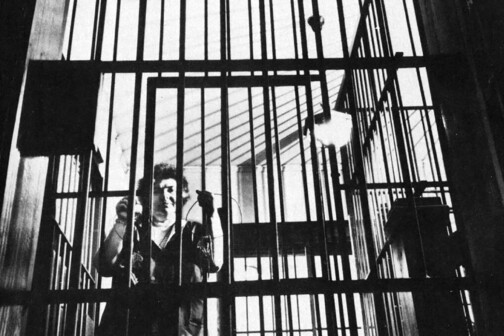

The names of the lynched men—Patrick Jennings, Samuel Smith, and Cato Miller—are now etched into the side of rust-colored pieces of metal arranged in a semicircle. A sundial sits in the center, allowing the shadows to draw the viewer’s attention to their names and those of others who were lynched in the city between 1853 and 1910. Jane Elkins, hanged on 27 May, 1853, one reads, marking the death of the person believed to be on Dallas’ first recorded bill of sale. There is also Reuben Johnson, lynched on December 27, 1874; William Allan Taylor, September 12, 1884; Allen Brooks, March 3, 1910.

For decades, their names were not found near the sites where they were killed. That changed in 2021.

For decades, their names were not found near the sites where they were killed. That changed in 2021, when the Texas Historical Commission recognized Brooks’ slaying with a historical marker at Main and Akard streets in downtown, close to where he was dragged to and hanged. Last year, a second marker went in the ground outside the Old Red Courthouse, where Brooks was thrown from a window while awaiting trial.

The new memorial, called Shadow Lines, opened to the public in Martyrs Park in March. A short walk from Brooks’ courthouse marker, this memorial is the work of artists Shane Allbritton and Norman Lee of RE:site Studio in Houston, whose public art often seeks to memorialize tragedies that communities have failed to reckon with. The title references the sundown towns where, Lee says, “cities weaponized darkness against Black folks.”

“The memorial was supposed to have this idea of hope, too,” he says. “Where there’s a shadow, there is light.”

The piece is part of a larger project spearheaded by the late local historian George Keaton, who spent his life centering Black history as part of Dallas’ history. His organization, Remembering Black Dallas, partnered with the Dallas County Justice Initiative, the city, and the county to plan a memorial for the site. On Saturday, June 22, Mayor Eric Johnson and other officials will gather at Martyr’s Park to recognize its own historical marker placed next to the sculpture.

It is a striking work of art, one that transports you away from the noise and bustle of its location as you take in its message, punctuated by a site-specific poem by former Dallas resident—and former poet laureate of Virginia—Tim Seibles. While it unfortunately sits on a less than tranquil site, obscured by the city’s development, its message is one Dallas must carry into its future, even if the viewer has to work a bit to seek it out.

This story was originally published in the July issue of D Magazine with the headline, “Shadow Lines.” Write to [email protected].