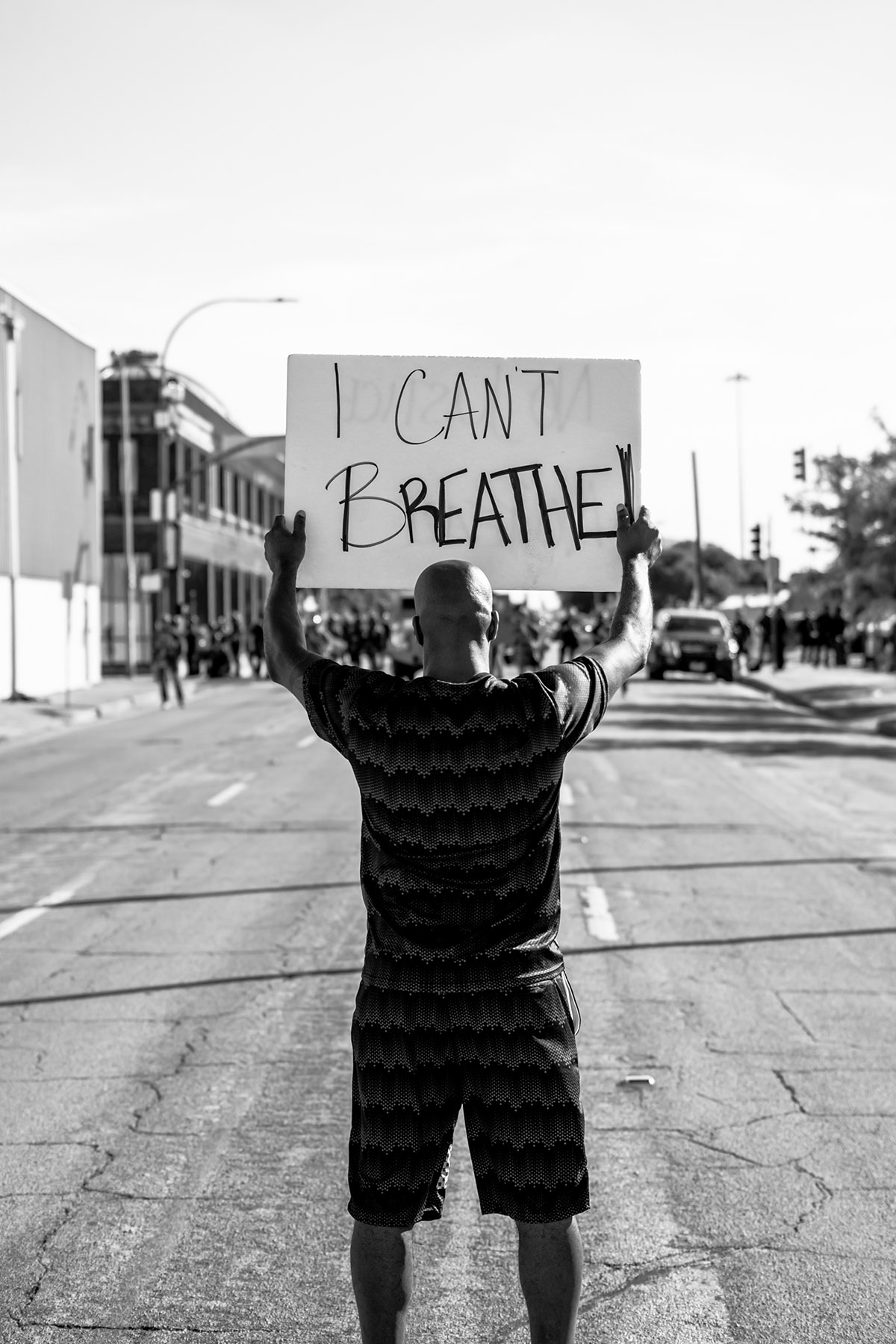

In the short time since the May 25 killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, we have accomplished that very American and inevitable thing of dividing ourselves into warring camps and points of view about it. But when the nation first saw the viral video—the knee on the neck, George Floyd calling to his mother while he was slowly killed—our response was a national shriek in unison.

That shriek of horror is still the truth, the heart and core of all this. But that same national unanimity of revulsion may mask another significant truth.

Every city in this country is unique, each its own family with its own long history, secrets, proud moments, and shame. Each city has absorbed this singular catastrophe in its own unique fashion.

For Dallas, there was never going to be a way the death of George Floyd could escape being bookended with 7/7/16—the night Micah Xavier Johnson, a 25-year-old Afghan war veteran, murdered five police officers and wounded seven more officers and two civilians during a downtown protest march.

In fact, for 10 seconds, let’s even try to forget politics. Forget philosophy. The rioting downtown over George Floyd’s death and the horror of 7/7/16 are inextricably bound in the consciousness of this city simply because we already know what can happen. We have seen it before. We have lived through blood, death, mayhem on our streets. Fury and grief are not mysterious strangers here. They are our companions.

And by the way, we are going to get to the questions of looting and provocateurs. Just give me a minute.

But first, a test question. I ask this knowing that the question will divide us into racial camps. And I guess I should tell you that, when the question was put to me, I came out White (surprise, surprise).

The 7/7/16 police deaths took place during a march to protest the deaths of two Black men at the hands of police. What were their names?

At the risk of sounding like a Joe Biden gaffe, I will surmise you are probably Black if you remember that the march in Dallas that night was to commemorate and grieve the shootings by police earlier that week of Alton Sterling in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and Philando Castile in St. Paul, Minnesota. If your answer is more like mine—the march had something to do with civil rights—then I will guess that you are probably White like I am.

That’s the problem now, says the Rev. Gerald Britt: “This is what happens because White folk don’t listen.”

Britt, a longtime Dallas pastor, community leader, and journalist, points to a direct human linkage between the 7/7/16 police deaths and violence that erupted in Dallas in the George Floyd demonstrations downtown: “Some of the very same people who were part of the demonstrations where the windows were being smashed now were part of that first march [in 2016]. It was a powerful, peaceful march.”

In downtown Dallas four years ago, the streets were jammed with people of all ages. One of the civilians shot (non-fatally) was a Black mother who had brought her children and a sister visiting from Michigan downtown to witness the power of history on the march—the kind of thing a parent does to instill hope and courage in children instead of cynicism and despair.

Britt does not begrudge anyone the terrible grief the city felt—and he still shares—for the human beings killed and injured that night. But he deeply regrets that the city didn’t have enough grief to spare for Philando Castile and Alton Sterling, whose deaths were the reason for the march.

“What I tried to tell the crowd downtown was, ‘Look, I am not going to tell you not to throw something through that window. But don’t give up on nonviolence. It’s the only thing that works in the long run.’ ”

John Fullinwider

“After that, nobody ever wanted to talk about Philando Castile and Alton Sterling,” Britt says. “We took it off the policy agenda. There were no public conversations about that.”

Britt does not condone the window-smashing, but in it he sees and hears a grief that was swallowed. “Because people weren’t allowed to publicly express their grief and their angst over Castile and Sterling and several incidents that went on before that, now all of that bile, if you will, has to be expiated, and it’s coming out ugly,” he says.

He wonders how Dallas might be dealing now with the death of George Floyd if things here had gone differently four years ago. What if our grief had been for every life unjustly taken? Why was there a line across our grief?

Britt says it’s not that we didn’t have other opportunities to reflect. In that same year, San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick began taking a knee during the national anthem before games to call attention to police brutality and racial inequality. The reaction of the president of the United States was to say, “Get that son of a bitch off the field right now, out, he’s fired. He’s fired!”

He wonders what things would be like now if White people in Dallas had gone the other way, if they had put Kaepernick’s knee together with the five dead and decided that both things formed an urgent call for fundamental change. “Imagine what would have happened if they had taken Kaepernick seriously, and then you started four years ago having a conversation about police reform, about criminal justice reform,” Britt says. “Imagine what would have happened if we had begun to seriously talk.”

But things did not go that way. In the wake of George Floyd’s death we saw rage, looting, and physical attacks in the streets in Dallas. I called John Fullinwider to talk about the looting and window-smashing because Fullinwider, a veteran of many civil rights battles, has been the city’s most steadfast proponent and organizer of nonviolent resistance for many decades.

I caught him right after he had addressed a crowd in front of City Hall. I was surprised by what he said to me on the phone. “Think of it like this,” he says. “William Lloyd Garrison (1805–1879) was a pacifist and an abolitionist, and he helped make abolition the point of the Civil War. John Brown (1800–1859) was a dedicated violent protester who had the goal of freeing slaves. He made his contribution as well.

“We can learn a lot from that,” Fullinwider says. “Each method of protest has its use and moments. You have to weigh that.”

Of the two alternatives, Fullinwider believes nonviolence has the greater power to change history. He points out that the Watts riots in Los Angeles, an occasion of terrible violence, destruction, and loss of life, and the historic Selma to Montgomery civil rights march based on nonviolence and passive resistance, both took place in 1965 and both riveted national attention.

“But what produced the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was sustained nonviolent resistance,” he says. “What I tried to tell the crowd downtown was, ‘Look, I am not going to tell you not to throw something through that window. But don’t give up on nonviolence. It’s the only thing that works in the long run.’ ”

We talked also about provocateurs. As a veteran of countless marches and demonstrations, Fullinwider says he always expects provocateurs to show up. “They are always there, all kinds, including police provocateurs.” But he made another observation that registered with me pointedly because of a story I had just seen the night before on a local TV station.

Reporter Jason Whitely at WFAA Channel 8 was making a great expose of the fact that he had obtained from police a list of people arrested in Dallas during the protests and that an examination of their home addresses revealed that many on the list were “not from Dallas.” Whitely announced this with a suggestive wobbling of the eyebrows, which, in combination with his COVID mask, put me in mind of the Merrie Melodies cartoon character Yosemite Sam.

Fullinwider had another take on the non-Dallas addresses, based on his observation of the crowds downtown. Rather than evidence of a sinister plot by outside agitators, Fullinwider says, people might take the list of suburban addresses for something quite different: “A lot of these conservative White folks out in the suburbs need to wake up to the fact that their kids are downtown demonstrating with Black Lives Matter.”

Hard to prove, I’m sure, but worthy of consideration.

Dallas is still a highly segregated city by almost every measurement, the cruelest now being the map of the impact of the pandemic. But at this point in its history, Dallas also has much of which it can be proud. Dallas now is the model for statewide school reform in Texas, a movement laser-aimed at the achievement of social equity and the defeat of racism.

The reforms in the Dallas public schools achieve success not by imposing harsh standards on children but by mining the rich vein of optimism and ambition already lurking in them if only we can find it. Someone who knows all about that vein of hope is Robert Pitre, a Black landowner and businessman in southern Dallas who has produced what he calls his “Life Guide America Map.”

Dallas is still a highly segregated city by almost every measurement, the cruelest now being the map of the impact of the pandemic. But at this point in its history, Dallas also has much of which it can be proud.

On the dark side of Pitre’s map are all of the corrosive influences that can make a life a living hell. On the green side are the values and achievements that can render a life productive and happy.

When he takes his map with him to speak to kids in poor Black neighborhoods in southern Dallas, he comes down hard at first by asking the kids how many of them have drugs in their families or neighborhoods, how many have family members in prison, how many see violence.

“It’s all of them,” he says.

His point is to show them a harsh truth. They were born to the dark side. They live on the dark side. He asks for a show of hands for how many want to stay on that side. “None of them,” he says. He asks how many want to go to the green side. “All of them,” he says.

He says he asked two 10-year-olds, a girl and a boy, why they wanted to go to the green side. “This little girl looked me straight in the eye, and she said, ‘I never knew until today what side I was on and what side I want to be on.’

“The little boy next to her said, ‘I want to go to college. I want to go to college.’ The kid pointed at the prison on the map and said, ‘I don’t want to go to prison. My daddy and both of my uncles are in prison. I want to go to college.’ ”

The Dallas school reform movement finds that hope in children and puts it to work. We are not a city without hope, and we are not a city that is doing nothing. But none of that makes the killing of George Floyd go away. The worst mistake now would be to find some convenient excuse—the looting, the people from out of town—to allow us to look away.

When I spoke with Gerald Britt, he and I talked about the police officer in the first viral George Floyd video who is standing to the right of the frame, his back turned partially to the killing. He is gazing off somewhere, his face a blank. We agreed we had seen that expression somewhere else before, but we couldn’t put our fingers on it.

He got it, and I agreed. We had seen it in the horrible postcards that were made of lynchings and sold as souvenirs. In many of them, there is some guy in the same pose, a little bored, his back to the lynching, looking off into the middle distance, his face a blank.

Like the face of the cop in Minneapolis, the face of the bored man with his back to the lynching expresses the one thing we cannot allow to overcome us again—impassivity in the face of horror.

Write to [email protected].