Dr. Sunday Eiselt—a field archaeologist, SMU professor, and former Marine—has a friendly disposition and long hair that falls to her waist. I went to meet her last summer on campus because she’d discovered something that I’d spent weeks searching for, something that had been missing for decades.

Inside Heroy Science Hall, I waited for her in the lobby and passed time by looking at various geologic displays and worn, oversize photographs of digs in Egypt. When she arrived, we made introductions and headed downstairs to the basement floor. As we began the descent, she turned and said, “We won’t be looking at any human remains today. I can show you artifacts, but no humans.”

She said this cordially but without leaving any doubt. It would take the next four hours to explain the restriction. Considering the enormity of the subject matter—13,000 years of indigenous occupation in North America and Dallas’ archaeological place in it—time passed quickly. There were more questions than available answers. She encouraged me to reach out to other people who work in local archaeology. But she did possess that one thing she’d invited me to see, an important piece of the puzzle I was trying to assemble.

Our meeting came about because of a single paragraph written by Edward McPherson, an assistant professor of English at Washington University in St. Louis. It appears in a book he published earlier this year, The History of the Future: American Essays, excerpts of which appeared in the Dallas Morning News in May. McPherson wrote: “Dallas came from nothing. Unlike surrounding areas, it was not a camp for Native Americans or prehistoric men. Dig and you find few artifacts.” I knew that assertion was wrong. The “Dallas came from nothing” trope has long been used by Dallasites to praise the grit and gumption of the Anglo businessmen who created the modern city. So in June, on D Magazine’s blog, I offered a counterargument to McPherson’s claim.

The short version: archaeologists, working on behalf of the city, unearthed nearly 3,000 prehistoric artifacts during the 2013 construction of the Texas Horse Park. The equestrian facility, located 8 miles southeast of downtown, is one of several amenities developed by the city on public land in the Great Trinity Forest. The recovery of artifacts at the site, contrary to McPherson’s assertion, is compelling evidence that prehistoric people made camps in the Dallas area.

That the recent find has gone unpublicized, I argued, isn’t due to the city’s lack of awareness of archaeological sites. It’s more a case of secrecy, which, from a legal standpoint, is partially justified (more on this later). I knew about the artifacts because I stay in contact with a group of citizen scientists that reminded the city, prior to Horse Park construction, of its statutory obligations when shovels meet earth. But in doing research for that McPherson blog post, I stumbled across an old News article about something quite remarkable.

In 1978, the city of Dallas paid two SMU archaeology students $10,000 (about $40,000 today) to create a compilation of all known prehistoric sites in Dallas. The sites were then plotted on maps. The compiled information, the News article said, “will be stored in a computer system accessible to builders and city planners” to be used to evaluate sites of potential archaeological or historic value prior to construction.

So I went looking for this 1978 database. But everywhere I turned, I found no help. When I asked Dallas’ chief planner and historic preservation officer, Mark Doty, he replied in an email: “I am not aware if city planners have access to any archaeological site database … but we do not have that for historic overlays and districts.” He also didn’t know of any city department that deals with archaeological sites in general, though he guessed that the city’s Trinity Watershed Management department might have some oversight of sites along the river.

As it turns out, two people outside of city government did know about the 1978 database project, but I wouldn’t find them until Eiselt found me. When my counterargument to McPherson went online, she posted a response in the comments section. If I was interested in “learning more about SMU archaeology,” she wrote, I should contact her. We exchanged emails. She received clearance from her dean. Then we locked in a date to meet. In addition to teaching and advising undergrads, Eiselt manages the SMU Archaeology Repository of Collections, or ARC. She said she would pull some prehistoric artifacts from the Dallas-Fort Worth area ahead of our meeting. And she said she had found something I also might be interested in: the original report from the 1978 project.

The report’s title, “Dallas Archaeological Potential: Procedures for Locating and Evaluating Prehistoric Resources,” partially explains itself. It’s a compilation of recorded sites and a probability index for encountering new ones based on soil types and proximity to the Trinity River and its tributaries. The report is also a step-by-step guide instructing the city on how to comply with federal laws as it pertains to archaeological resources and federally funded projects.

At the end of our meeting, Eiselt scanned the report and emailed me a redacted copy that didn’t include maps of sites where artifacts had been found. Later, city staff sent me the same report and inadvertently didn’t redact the maps. It was a telling mistake.

Right now, whether by design or dereliction, the city of Dallas is not paying attention to some of its most important history. There has been a lot of talk lately about Dallas making a 10,000-acre park along the Trinity. But as we rush to plan for that, we, as a city, have a woefully inadequate understanding of who came before us and what lies beneath.

Five days after my visit with Eiselt, the Dallas City Council voted down a decades-old plan to build a toll road between the levees in the Trinity River floodway. That turn of events, welcome as it was, greatly complicates the discussion of Dallas archaeology. With the road out of the picture, the development of a park along the downtown stretch of the river is coming sooner rather than later. And there’s discussion that a limited government corporation, or LGC, will oversee the park’s development and maintenance. An accelerated plan to build the park should cause concern. According to the 1978 report, “most of the 116 [archaeology] sites in Dallas cluster along the larger drainages—Mountain Creek, Trinity River, Elm Fork of the Trinity, White Rock Creek and Five Mile Creek.”

More recently, in 2014, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers identified eight archaeological sites in the Dallas floodway. Location of the sites is withheld from the general public under the Archaeological Resources Protection Act of 1979. But both the 1978 report and the recent Army Corps survey offer clear proof that prehistoric people in the Dallas area lived close to water sources. If there’s any chance of learning more about our area’s prehistoric past, the city—and, by extension, the LGC—needs to provide assurances it will be attentive to potential archaeological sites as it excavates lakes and builds concrete amenities near the river. It’s possible the sites may contain human remains.

While the city is required by the Antiquities Code of Texas, established in 1969, to undertake a cultural resources survey prior to construction on public land if there are any previously recorded sites in the project area, there is no guarantee resources will be protected. The artifacts recovered at the Texas Horse Park were preserved only because a group of concerned citizens—Ben Sandifer, Tim Dalbey, M.C. Toyer, Becky Rader, brothers Hal and Ted Barker—insinuated themselves in the survey process. They pushed the city for a more thorough site excavation and offered historical corrections that were eventually included in the final report.

That report, which describes what can be known about the artifacts and the people who made them, is not available through the city. The department that Doty, the Dallas chief planner and historic preservation officer, mentioned in his email, Trinity Watershed Management, did not respond to my questions about the availability of the report. The Texas Historical Commission, the state agency for historical preservation, did. A copy of the report, titled “Cultural Resources Survey for the Proposed Texas Horse Park, Dallas County, Texas,” is held at SMU’s Fondren Library. It is lightly redacted to protect the precise location of the site, as required by law.

When I met with Eiselt, she broke down for me the legal nuts and bolts of archaeological practice. She also gave me a quick history of the transformative changes in the field over the last 50 years, an evolution partly driven by SMU. Speaking generally on the nature of archaeology, she explained that artifacts alone can’t tell the complete story. Careful study and documentation of where cultural objects are found provide context. “If people come in and take a bulldozer to a site,” she said, “all of those intricate relationships that exist, that actually tell us about behaviors, how people lived in the past—which is what we are interested in—can be destroyed, possibly lost forever.”

If there are human remains, she said, it becomes a more complicated matter. Affiliated tribes would need to be consulted. “It’s better to have those alliances forged ahead of time,” she added. Meaning, before excavation begins. “Archaeology as we know it began to change radically in the 1960s with the American Indian Movement, and one of the central concerns is how their ancestors were being treated. As the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act worked its way through to passage in 1990, the whole debate with archaeology kind of unfolded in a pretty volatile, very contentious period of time where Native people were trying to assert their sovereignty rights.”

Eiselt was an undergrad when NAGPRA passed, and she’s had lots of experience interacting with tribes. The act provides assurances that tribes are consulted when deciding the fate of ancestral remains and associated funerary objects.

Other archaeologists I talked to had similar things to say about the practice of modern archaeology, or what is called the “new archaeology,” based on the work of pioneering archaeologist Lewis R. Binford. The author of more than 18 books, Binford taught at SMU from 1991 until retirement, in 2003. Scientific American called him the “most influential archaeologist of his generation.”

The new archaeology, unlike past practices, is less about the tangible ownership aspects of artifacts found at sites, and more about a scientific, interdisciplinary approach to learning about how people in the past lived, interacted, and adapted. Seen in this light, each site, if carefully studied, can provide continuity between people and places in an ever-expanding narrative.

That’s a high bar to clear when considering the pace of new projects in the Trinity Forest and along the Trinity River. And so far, the city’s interest in archaeology appears to be driven by statutory requirements, not a quest to understand and educate. There’s nothing to suggest anything illegal transpired during the recent excavation at the Texas Horse Park, but it did take citizen watchdogs to make sure it was done satisfactorily. If the city were practicing Binford’s “new archaeology,” more time would have been needed to examine sites—which might require postponing planned construction, assembling an interdisciplinary team, and starting a conversation with the appropriate tribe(s).

While the artifacts from the Texas Horse Park have been safely stored at a state-approved facility (as state law requires), and a final report, called a cultural resources survey, has been prepared by a professional archaeological firm (as state law requires), there’s been no cohesive narrative presented to the public about the site (though the city conducts cultural resources management on our behalf, it is not required by law to publicize it). And even if the public knows where to look and what to ask for, the archaeological record is inaccessible in other ways. The nearly 3,000 artifacts reside at the Texas Archeological Research Laboratory, or TARL, on the UTA campus. To see them requires a road trip and an appointment. Images are not available online. The report on the artifacts, available at SMU, is written in technical language. While informative, it can be difficult to penetrate.

There is, however, an archaeological record with no gatekeepers. It is a legacy close at hand, waiting to be picked back up.

Eiselt’s offer to me had been to learn more about “SMU archaeology.” After spending time on campus, in her laboratory in the basement of Heroy Science Hall, I understood why. All roads to North Texas archaeology lead to SMU. And to understand what is happening in the present, one must look to the past through the historical contributions of the Dallas Archaeological Society.

The organization was formally organized in 1940 and consisted of collectors and “amateur” archaeologists who had a profound interest and commitment to archaeology. (The “amateur” label is no longer used; the preferred term is “avocational.”) Most members were tradesmen or professionals working in other fields. Early founding member R. King Harris, for example, worked as a locomotive engineer. In the beginning, the society met at members’ homes. Later, they met once a month on the SMU campus. Claude C. Albritton, a geologist and dean of the Graduate School of Humanities and Sciences, along with Ellis Shuler, provided the SMU connection. Meetings continued until 2012, the year the group folded. Dalbey, one of the people who forced the city to dig carefully at the Texas Horse Park, says that aging members were no longer able to participate. Also the climate at SMU changed. “The anthropology department was shifting its emphasis away from archaeology, specifically Texas and local archaeology,” Dalbey says. “This was a source for much of the interest in the DAS and contributed many members.”

The society left an extensive written record of its activities, which spans more than seven decades. When members weren’t getting their hands dirty in the field, they were prolific writers who published their own semiannual journal, The Record. Some issues include field notes, maps, and descriptions of sites from North Texas. In fact, the work of Dallas Archaeological Society members provided the groundwork for the 1978 project that was funded by the city.

“For the Dallas site data,” wrote the report’s authors, “we are especially indebted to R.K. Harris, whose vast knowledge of the archaeological resources of this area is unmatched. His records, dating from the late 1930s, provided not only valuable information, but a perspective of the resources which is no longer available.”

SMU’s Fondren Library holds most issues of The Record. Eiselt says gathering them in one collection has been an ongoing project, but there are still a few missing issues. Building an online resource of the journal or even an index is out of the question. There’s no budget for it.

Prior to meeting Eiselt, I knew a little bit about the Dallas Archaeological Society from reading old newspaper articles. I knew considerably less about archaeologist Fred Wendorf, whose excavation photos I studied in the lobby. After Eiselt showed me black-and-white photos from the archives—Wendorf at Fort Burgwin in New Mexico and Harris managing collections at SMU—she suggested I pick up a copy of Wendorf’s memoirs, Desert Days: My Life as a Field Archaeologist, if only for the pages describing his first contact with Harris.

In Desert Days, Wendorf wrote about meeting Harris by chance at the 1936 Texas Centennial Exposition at Fair Park. Wendorf was then a 12-year-old living in Terrell, Texas. Harris, 24, was heavyset and wore browline glasses. When he wasn’t running trains for the Texas Pacific Railroad, he was in the field studying archaeological sites and taking notes. At Fair Park, they crossed paths at the Hall of State. Harris had an exhibition of artifacts on display. When he spotted Wendorf hanging around the exhibit, Harris asked if the boy collected arrowheads. Wendorf answered in the affirmative and told him about his growing collection gathered from the fields around his hometown. Harris then asked: “What sort of records do you keep, Fred? Do you plot your sites on a map?”

Harris didn’t hold a degree in archaeology (few did in Texas in 1936), but his gentle instruction that day on how to properly document sites would have far-reaching impact. “From that time on,” Wendorf wrote, “I began numbering my sites and putting site numbers on the artifacts as I found them. I obtained maps (the county soil maps were particularly helpful) and recorded the site numbers on them. … I began to tell everyone I was going to be an archaeologist.”

Wendorf did indeed go on to become one of the most renowned archaeologists of the 20th century. While he spent his professional career saving an extensive body of knowledge of the prehistory of Egypt and Sudan from certain inundation from the Aswan High Dam project, built in the 1960s, Harris did the same sort of work in North Texas. Harris and other Dallas Archaeological Society members saved knowledge of prehistoric sites in advance of reservoir projects in Dallas County (Joe Pool Lake), Denton County (Lake Lewisville), and Collin County (Lavon Lake). Sometimes the work was in support of official survey work; other times, they did it just because they cared.

Harris and Wendorf would come together again, in the 1960s, some 30 years after that fateful meeting at Fair Park. In 1964, Wendorf was hired as the first professor in SMU’s new department of anthropology. A few years later, Harris became the curator of the department’s collections.

Wendorf retired from SMU in 2003, the same year that Binford, the father of “new archaeology,” retired. Harris retired as curator in 1970, though he continued in his capacity as consultant until his death, in 1980. Both men helped nurture and build the archaeology program at SMU, but neither left his considerable collection—artifacts, maps, notes—to the university.

Harris’ collection is housed at the Smithsonian Institution in Suitland, Maryland. According to Smithsonian collections specialist Dr. James Krakker, Harris’ Dallas County collection consists of 3,406 items from 75 sites. He described the items to me as the type of artifacts “common to prehistoric habitation sites”: chipped stone tools, projectile points, scrapers, drills, shards from ceramic vessels, and faunal remains. “We don’t normally give out specific site locations,” he said, “but as you would expect, the sites are along the rivers in the county.”

Placement of Harris’ collection came down to financial necessity. His combined pensions from the railroad and SMU amounted to a paltry sum, and the Smithsonian could provide a small trust for his spouse as well as state-of-the-art care for his collection. Wendorf’s collection went to the British Museum in London, because in May of 2000, he wrote in his memoirs, “the SMU administration decided it did not want the expense and responsibility of caring for my Nubian artifact collection, and asked me to find a suitable home for it.” The British Museum gladly accepted, and by September 2001, millions of items were shipped abroad.

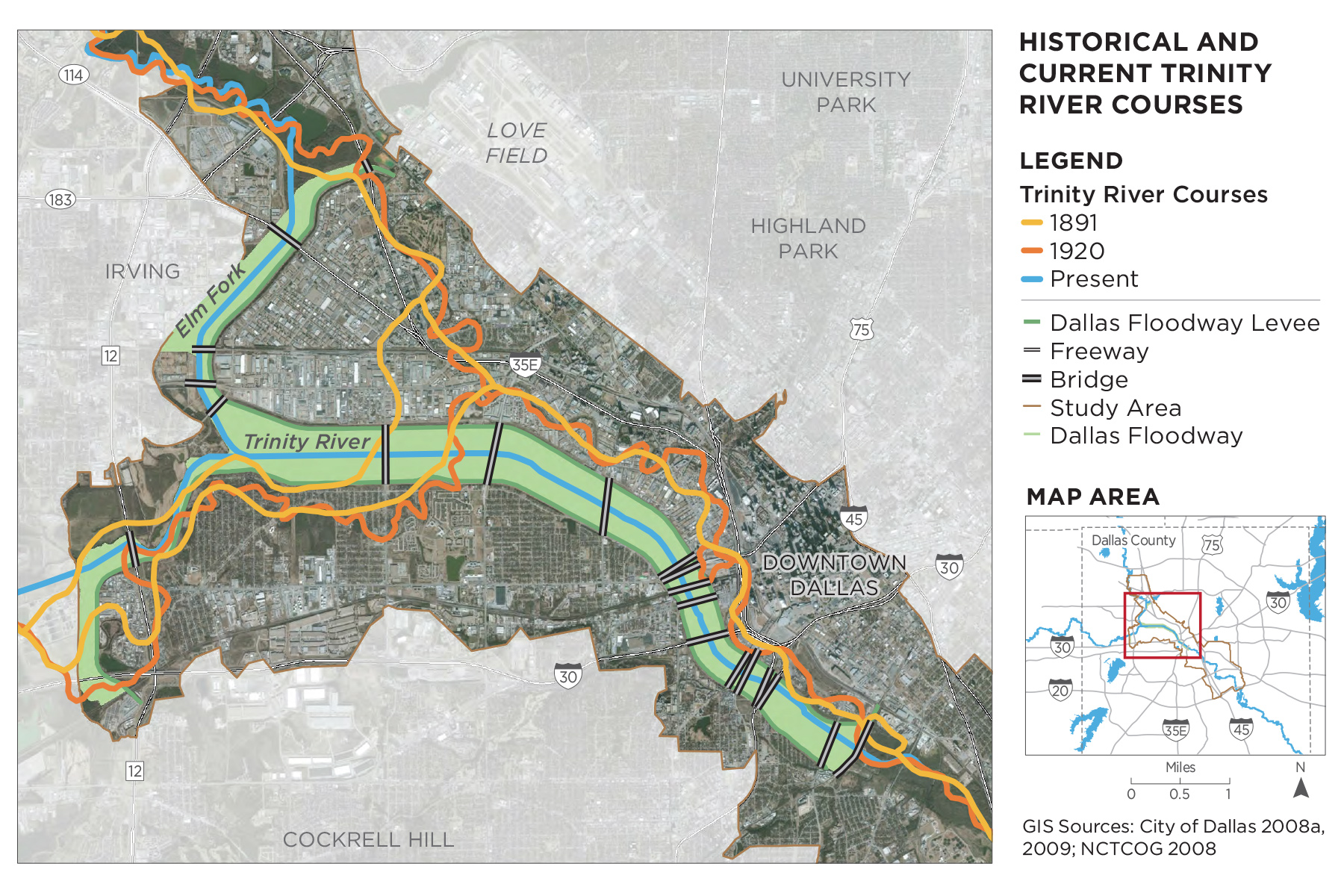

At the height of Harris’ and other Dallas Archaeological Society members’ collecting days, they could excavate freely on public land (which also meant looters could, too). Lack of controls also meant the city had no legal obligation to rescue archaeological resources during the relocation of the Trinity River from its natural channel in 1928. The river was moved a half-mile west for purposes of flood control and land reclamation from its natural, meandering channel to a straight man-made channel. Excavated dirt was used to build levees.

After World War II, at the urging of archaeologists, a preservation ethic began to emerge that decades later led to legal protections for cultural resources. One way to preserve nonrenewable, cultural resources is through “salvage archaeology,” the practice of documenting and excavating sites in advance of construction on large earth-moving projects such as reservoirs, pipelines, and highways. The practice is now referred to as “cultural resources management,” and, by law, subdivisions of the state (including the city) must comply with state and federal preservation mandates. For that reason, cultural resources management is also called “compliance archaeology.”

One of the first laws to codify the preservation ethic is the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, or NHPA. The act recognizes that government controls are needed to protect cultural resources “in the face of ever-increasing extensions of urban centers, highways, and residential, commercial, and industrial developments.” Those resources have value, according to the act, because “the historical and cultural foundations of the Nation should be preserved as a living part of our community life and development in order to give a sense of orientation to the American people.”

Harris practiced salvage archaeology before it had a name. There were no laws that compelled him or other Dallas Archaeological Society members to rigorously document sites or to be conscientious stewards of cultural resources. Somehow they knew it was the way to go about it. And because of their work, an archaeological record exists today. “Many of the sites [Harris] recorded and collected from no longer exist due to residential and industrial expansion in the county,” says the Smithsonian’s Krakker. “So without his work nothing would be known about or preserved from many prehistoric habitation sites. … Needless to say a very important research collection for Texas.”

The path Eiselt traveled to reach Dallas, Wendorf paved. In 2006, she had just finished her dissertation on the history and archaeology of the Jicarilla Apache of New Mexico when she was asked to teach a summer course at an SMU campus in Taos. She ended up teaching field school there for five years. From New Mexico, she made her way to Dallas as a visiting professor.

The connection to Wendorf is in the back story. In the 1950s, he wanted to start a field school in New Mexico, a place where students could gather for an intensive few weeks learning excavation skills from experienced archaeologists at actual sites. He met with a lumberman named Ralph Rounds, who owned 9,000 acres 9 miles outside of Taos, to pitch the idea. Rounds was agreeable. They built a facility together on a portion of land that contains an old fort, Fort Burgwin, and remnants of Pot Creek Pueblo. The facility eventually became the campus where Eiselt first taught for the university. Today it is called SMU-in-Taos.

When I met Eiselt, whose expertise is in the archaeology of the American Southwest, she told me to contact two men, Alan Skinner and Wilson “Dub” Crook, to learn more about prehistoric sites along the Trinity River. Skinner, who also arrived in Dallas from the Southwest, has practiced archaeology in Texas since 1968, the year he came to SMU to study for his doctorate and began working with Harris. Crook, an avocational archaeologist, recently co-wrote a book on the prehistory of the East Fork of the Trinity River, documenting 20 major village sites and numerous seasonal campsites in Collin, Rockwall, Dallas, and Kaufman counties.

It turns out that there weren’t two authors of the 1978 report; there were actually three. Skinner’s name appears above the other two on the title page because, at the time, he was the director of SMU’s Archaeology Research Program. The city sent requests for proposals to undertake the survey to three local academic institutions with archaeology departments; SMU had been the only one to respond.

He told me that he considers Harris his mentor in Texas archaeology. “He served as a great adviser during the time that he was at SMU, and I relied on his advice after he retired,” he says. “He had visited lots of North Texas sites and had brought many collectors together in the DAS. He had a good memory for where things came from.” In retrospect, he says, he was probably Harris’ last student.

Skinner left SMU in 1980 and now operates his own cultural resources management firm, AR Consultants. When I asked him about the 1978 report, he says he has backed off the conclusion in the report that the current river channel has high archaeological potential. “Of course the original channel is not where the river currently is,” he wrote to me, “and we have numerous good studies which document buried prehistoric sites along the old channel and few along the channelized stream.” A Trinity Parkway environmental impact statement from 2005 drives this home: “The most likely locations to encounter buried prehistoric archaeological deposits are along the meanders of the old Trinity River.”

The buried prehistoric sites, he says, those of the Clovis age, would be found in late Pleistocene sediments. Clovis culture appeared some 12,900 to 13,500 years ago. When I asked him about the depth of those sediments, he responded, “There is some evidence that late Pleistocene sediments in the old river channel may be as deep as 60 feet below the flood plain.”

The almost 3,000 artifacts recovered in the Trinity Forest were found upland, and not far below the surface. The culture(s) who produced and used the artifacts are considered prehistoric, but those people lived much more recently than the Clovis culture. The latter group dates back tens of thousands of years. Distinctive projective points called Clovis points have been found throughout North America at 1,500 locations, and the oldest securely dated points have been found in Texas. There are two confirmed Clovis sites north of Dallas County, along the Elm Fork of the Trinity River (the Lewisville site, Lake Lewisville, Denton County; and the Aubrey site, Lake Ray Roberts, Denton County). This means that the evidence of one of the oldest cultures in North America might lie buried beneath the alluvium, within eyesight of the Margaret Hunt Hill Bridge.

The other person Eiselt suggested I call was Crook. Our two-hour conversation led in similar directions as my talk with Skinner, and it began with a discussion of Clovis culture. He says Dallas County archaeology is part of a much larger narrative called The Peopling of the Americas. “No one has written a concise prehistory of the area to date,” he told me. “Dallas County does have Clovis-age sites—purported to be Clovis sites—in proximity to the Trinity River.” That includes the Elm Fork, the main stem, and the area where the East Fork feeds into the main, just outside the county boundary.

In 1985, SMU archaeologist Dr. David Meltzer initiated the Texas Clovis Fluted Point Survey. The current tally of Clovis points reported in Dallas County is six. That number is low, says Crook. There are many more that haven’t been reported and are held by “private collectors who couldn’t care less about the science.” He speaks with authority on the matter; his father and Harris are attributed as the source of the six Clovis points reported in the Texas study.

Crook lives in Kingwood, a suburb of Houston, but he grew up in Dallas. His father, Wilson “Bill” Crook Jr., and Harris were archaeological partners, and as a boy, Crook often accompanied them on digs. The Crook household, he says, was a vibrant center for Dallas Archaeological Society members and SMU faculty. “It was a fertile environment and a time when camaraderie meant something,” he says. Crook, a degreed mineralogist, now retired, says Harris was his mentor from an early age. Harris would often say to him, “There is no such thing as knowledge if it’s not published.”

All roads to North Texas archaeology lead to SMU. And to understand what is happening in the present, one must look to the past through the historical contributions of the Dallas Archaeological Society.

Ben Sandifer is a master naturalist and one of the people who forced the city to pay attention to what it was doing when it moved dirt to build the Texas Horse Park. He hikes through the Trinity Forest nearly every week. Few people know it like he does. On a trek in July, after a big rain, he found an arrowhead in a gravelly area. He left it where it lay. He says, “Dallas has an immense archaeological history, a profound history that tells the tale of ancient humans.” But he worries the history is not being cared for properly. For starters, he says, the city doesn’t have an archaeologist on staff. And the department that oversees projects in the area, including cultural resources management, has proven itself to be inept.

“I don’t think Trinity Watershed Management has any ability to see value in archaeology,” he says. Sandifer and others were confident that artifacts would be found in the Horse Park project area because they all had read Dallas Archaeological Society member Forrest Kirkland’s surveys of the area from the 1940s.

Even if Sandifer and other citizens continue to perform their watchdog roles in advance of construction, any material objects that are collected by professional archaeologists on behalf of the city will only be sent away. It’s likely they will never be shown publicly in Dallas. The Perot Museum of Nature and Science—the only museum in the city suitable for exhibiting Trinity River archaeology—sent a statement explaining its position on why it doesn’t have anthropological or archaeological exhibitions. According to the director of lab paleontology, Dr. Ron Tykoski: “Native American remains and objects, as well as other ethnological specimens and artifacts, often have extra levels of regulation, as well as handling and care requirements, beyond other collections’ objects. … The Perot Museum does not currently have a research focus in those areas, and, as a result, our staff does not require additional expertise in handling such culturally sensitive objects.”

It’s worth remembering H. Ross Perot’s interest in relocating the Museum of the American Indian in New York to Dallas in the mid-1980s. Had he succeeded, Perot would have built a $74 million archaeology museum on a 10-acre site. Plans included exhibit spaces, a research center, fumigation chambers for artifacts, and 88,000 square feet of storage space, including cold storage for furs and feathers. The proposal to move the museum out of state proved controversial and was ultimately rejected.

As for SMU, Eiselt has the expertise but not the funding for exhibiting artifacts. She says, though, that she’d be willing to partner with other organizations. The ARC, she says, also can’t take in artifacts and other items from compulsory archaeology performed by the city. “Right now, all Dallas-related archaeology collections,” she says, “excavated as part of projects done in this county and surrounding counties, are sent to TARL in Austin.”

For the ARC to take on those collections, Eiselt says, it would have to be certified by the Texas Historical Commission. That would require considerable upgrades: appropriate staffing, facilities with environmental controls, and creation of inventories that help make information about collections available to the public and other researchers. “We don’t currently have the resources and support to achieve this at SMU,” she says. “However, our long-term goal is to gain certification. My dream is that we can one day accept Dallas collections and become the leading repository for Dallas heritage in the state.” SMU is the logical first choice, she says, “given our long history in local archaeology that goes back to the 1960s and Fred Wendorf’s pioneering vision.”

The 1978 report “Dallas Archaeological Potential,” built on the work of Dallas Archaeological Society members, is optimistic in tone. A recommendation on page 72 is a reflection of a brief moment in time when archaeologists were asked for their studied opinion: “Once important sites are known it then becomes possible to manage them effectively. Where feasible, sites should be acquired and included in parks, greenbelts, and floodways where they can be preserved. … In the future these sites can be developed, excavated, stabilized and made available for the appreciation of future generations.”

Today there is no institutional memory of the report inside city government, which means the work of the Dallas Archaeological Society has also become a forgotten relic. For decades the city has made and remade plans for a park in the floodway and amenities in the Trinity Forest. The one aspect that hasn’t yet been planned for might be the most important: a duty to our ancestors.

Get the D Brief Newsletter

Author