Ours is the only city in the country that evokes a hair color. Just how did that happen?

There are all kinds of blondes. Honey blondes, golden blondes, strawberry blondes, platinum blondes, suicide blondes, dirty blondes, dishwater blondes, dime-store blondes, million-dollar blondes, all-American blondes, airhead blondes. But there is only one Dallas Blonde.

The Dallas Blonde is not about the hair, as we’ll see, but the hair is the window to her soul. The Dallas Blonde, first of all, is very blonde. Of the 37 shades of blonde known to professional colorists, she runs from Golden Platinum (palest of the pale) to Light Ash to Golden Strawberry, but she wouldn’t be caught dead as a Butterscotch or a Brownish Blonde. Her head is like a scrim of reflected light, and she’s forever in search of the purest, palest aura.

But the Dallas Blonde is not just concerned with color. She’s also mad about volume. I don’t want to use the term “big hair,” because that would be so ’80s, but Jennifer Aniston, for example, would never be mistaken for a Dallas Blonde because she has entirely too few follicles. The straightened coif of a Dallas Blonde might zigzag across the forehead, or the Tower of Power Blonde might pouf it up into the ozone, but there’s a Hair Statement being made here. This is blondeness with some heft. Minimum blow-dry time: 45 minutes.

Finally, the Dallas Blonde is infinitely groomed. She’s highlighted, she’s teased, she’s styled, she’s shagged, she’s razor-cut, she’s arrayed with barrettes and earrings (earrings for a Dallas Blonde are not jewelry; they’re a frame for the hair). And, above all, she’s accessorized. She’s got the shoe thing going on, and the purse thing, and the precise shade of lip gloss to set off the theological marvel that sits atop her cranium. Because, yes, being blonde in Dallas is a religion, and the hair itself is the holy of holies in the Blonde Temple—everything points thence.

Do you think I overstate my case? What about California blondes, you might ask? What about Swedish blondes? Didn’t they invent blondeness? What about Norma Jeane Baker, who morphed into Marilyn Monroe when she went blonde and made it a standard of seduction? I would argue that all of these blondes are actually precursors, early prophets and prototypes, and that in any event, they don’t hold up as avatars of blondeness on closer inspection. Blonde jokes were invented for the California blonde, who is all empty-headed beach-dwelling exuberance, a girl with a frozen smile and a cheap bikini who inhabits the erotic dreams of surfer dudes. The Scandinavian blondes cancel themselves out by sheer overkill. I lived in Denmark for a year and became sated with the sameness of it all. They don’t enhance their blondeness. They don’t live blonde. They just happen to be victims of a recessive gene.

The Dallas Blonde, on the other hand, has made a choice to be blonde. She hasn’t been born into the breed; she’s clawed her way toward perfection. There’s no such thing as a wispy Dallas Blonde, nor will you find a Dallas Blonde who could be called retiring, introspective, or mousy. A Dallas Blonde is always the girl who smashes the beer bottle on the tabletop when trouble arrives, not the one who clings to her boyfriend’s lapels. A Dallas Blonde occupies major space in the room. She might be a little hippy. She’s never fat, but she might be what’s called thick, or chunky, or just big-boned. You can’t carry Dallas Blonde hair on the chassis of a Ford Focus. And even if she’s razor-thin, the overall impression is that she takes the stage. She’s here to be reckoned with. Attention must be paid.

I know what you’re thinking. “He’s been giving this subject entirely too much thought.”

Yes, I have. I’ve been wallowing in it for a while now. It’s Gene Street’s fault.

It’s like this. At the Cool River Cafe located in the international terminal of DFW Airport, the legendary restaurateur sometimes personally works the greeting station. Since the place is always abuzz with tourists and business travelers, and since Street is known for being a man who’s never passed up a conversation, he uses the opportunity to ask people the question “What do you think of, when you think of Dallas?”

No. 1 answer, for Americans, is “the Cowboys.” (No. 1 internationally is “J.R. Ewing.” Yes, it’s still in overseas syndication.) Close behind are “Business” and “Mark Cuban.”

Blondes are No. 4. No other city in America evokes a hair color. And Street says it’s equally true regardless of nationality. Russians, Australians, South Africans—they all associate blondeness with the city. This is the case even if their primary exposure is through the old Dallas TV series—odd, since the only blonde regular was the fourth-billed female, Charlene Tilton. (Miss Ellie doesn’t count. Although, if we had space enough and time, I could wax lyrical about the sub-category called the Matriarchal Dallas Blonde, best represented by Ebby Halliday and Kim Dawson, two women whose blondeness so penetrated into their genes that it became a sort of distaff corporate jet fuel.) At any rate, Gene Street swears by the scientific accuracy of his survey. (For more on his fixation on blondes, see Street’s essay below.)

But how does such a thing happen? How does a city become known for its pilar pigmentation?

As a matter of fact, we know exactly how such a thing happens. Not only do we know how it happens, but we know precisely when it happened—on Monday, November 10, 1975. But not so fast. Because to understand what happened that day, you need to know a little history, the foundation on which that epic moment was built. Let’s start in the year 1937. By then the Dallas Blonde was already well enough established to trigger one of the city’s most famous acts of civil disobedience. I speak, of course, of the All-Blonde City Hall Sit-In.

For the second year of the Pan-American Exposition, part of the Texas Centennial celebration that resulted in the construction of Fair Park, the producers announced that the Texanitas, or official hostesses, would be brunettes only, in keeping with the Latin theme of that year. Helen Ramsey, a 16-year-old blonde who had worked as a Texanita the previous year, was incensed.

And Helen Ramsey was not just any Dallas Blonde. Helen Ramsey, at the age of 15, had been selected for her perfectly proportioned body as the human model for Texas, the 20-foot sculpture based on the Venus de Milo that stands at the head of the Esplanade of State. Let me put this into perspective. The sculptor—Lawrence Tenney Stevens was his name—could have used the Venus de Milo as his inspiration for the female figure of the state, he in fact intended to do just that, but he found that a nubile 15-year-old Dallas girl was actually more feminine and so he used a bicameral inspiration, from a) the Louvre and b) a Dallas high school. Need we re-emphasize the power of the Dallas Blonde? At any rate, the upshot was that, a year later, the new “brunettes only” policy would not only discriminate against blondes, it would make the symbol of Texas ineligible for hostessing duties.

Ramsey, true Dallas Blonde that she was, didn’t waste any time making lame brunette gestures like, say, writing letters to the editor. She gathered together six other blondes, and they showed up at City Hall, talked their way past the receptionist by pretending to have an appointment, then took seats in Mayor George Sergeant’s empty inner office. When the mayor arrived for the day, they announced that they weren’t leaving until blondes were hired at Fair Park.

At first the mayor humored them, acting amused and sympathetic and assuming that they would eventually go away, having made their point. They didn’t leave. He conducted business throughout the day with the aggrieved blondes sitting their ground, legs demurely crossed. Eventually the mayor put in a call to the Exposition director, Frank L. McNeney, to relay the blondes’ point of view—that blondes are just as typical of Texas women as brunettes “and we refuse to be discriminated against.” Unfortunately McNeney was out of town, so the mayor suggested that the blondes come back the following day.

They would have nothing of it. They announced their intention to stay the night. By this time various downtown restaurants were sending food over, and hotels were offering rooms for the blondes—but the blondes declined the rooms, saying it was necessary for them to stay within the confines of City Hall. They did ask for a chaperone, however, and a high school teacher volunteered to stay with them for as many nights as they needed to remain. When the mayor suggested they were taking the joke too far, the blondes refused to be insulted and cordially invited him to breakfast. The chief of police sent a guard to protect the blondes’ rights. Blonde sympathizers started massing on the streets outside.

Finally, everyone gave in at once. The Exposition announced that the “brunettes only” edict was no longer in force. In less than 24 hours, Dallas Blondes had achieved their purpose.

This was perhaps the finest moment of what I will here define as the first of three types of Dallas Blondes. These seven women were prepared to go the distance—with a chaperone. These were exemplars of Church Choir Blondes. They might fool around, but you’ll have to meet them at Sunday School to find out.

But there’s another strain of Dallas blondeness, a more sinister strain, and it comes from the decades when blondeness was still a mark of shame, the Dallas pre-history when the little town at the crossroads of the Trinity was populated mostly by immigrants moving westward from the South. You had some Irish redness that would sometimes transmogrify into a sallow washed-out blonde, and you had some English peaches-and-cream matrons who carried the DNA of invading Viking rapists. But there were very few blonde girls, and they were regarded as mongrels.

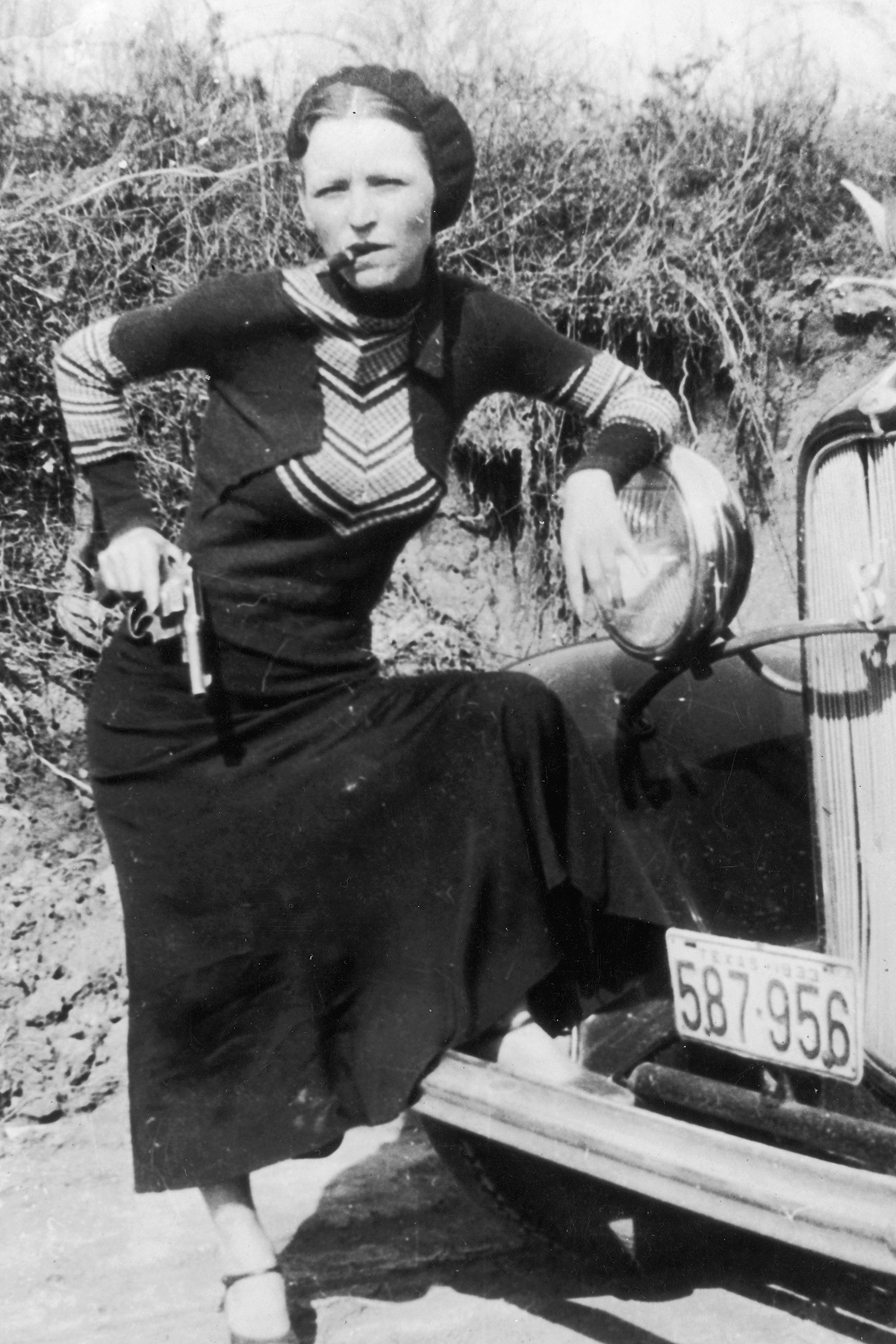

This sub-species reached its apogee in the life of a West Dallas girl named Bonnie Parker, who read romance novels and had a tattoo above her right knee expressing her eternal love—for a man she ran away from. No reason to re-tell the familiar story, but I would call attention to two Dallas Blonde traits. First: the only time Bonnie was captured by police—after a botched armed robbery in Kaufman—the Kaufman grand jury no-billed her. No doubt she looked like the helpless pawn of a no-good man at the time. The second point: in their penultimate homicide, on a lonely stretch of highway near Grapevine, it was Bonnie, not Clyde, who put two shots of a sawed-off shotgun into the head of a police officer at point-blank range. Her reported remark at the time was, “Looka there, his head bounced just like a rubber ball.”

By the way, for those wondering whether I’m talking about the Faye Dunaway version of Bonnie or the much more played-out-and-used-up version you find in the photographs, my answer is: both. The real Bonnie was 4-foot-10, 85 pounds, but Faye Dunaway’s portrayal was correct because she was a goldurn Dallas Blonde! She didn’t need to comb her hair.

Now. I’m not saying that it takes 13 murders to qualify as the ultimate Blonde Bitch, but if Texanita Helen Ramsey is the goddess type, the ultimate Church Choir Blonde, then Bonnie Parker, the hash-slinging murderess from south of the river, is the anti-goddess. Of course all Dallas Blondes have a little bit of both. It’s a spectrum, and men usually know which end of the spectrum the new blonde lives on.

But Helen Ramsey and Bonnie Parker, the two extremes, are only pale versions of the third type: the Ultimate Dallas Blonde. And for this type we have to look first at the career of Mary Louise Cecilia Guinan, born on the open prairie between here and Waco in 1884 to Irish immigrants (virtually the only source of blondeness at the time) and, in her lifetime, a tomboy, a rebellious Catholic schoolgirl, a riding roping Wild West showgirl, a chorus girl, a Gibson Girl in vaudeville shows, one of the few females ever to star in silent-film westerns, and, most notably, a boozy throaty singer in Prohibition-era speakeasies, where she greeted customers with her trademark “Hello, suckers!” Under constant surveillance by federal authorities, including the same FBI agents hunting Al Capone, “Tex” Guinan would steadfastly deny that any alcohol was ever sold at any club where she worked, would never be successfully prosecuted (although she did some minor jail time), and despite numerous raids on every place she worked, would make $700,000 in the year 1926 alone. Like her rival Mae West, she would eventually be shut out of movies by the Breen Office, and by the early ’30s she’d become so notorious for her illicit love affairs and run-ins with the liquor authorities that her traveling show was banned from several European countries and she was reduced to doing road shows in North America. The ultimate good-time girl, she died on the road, at age 49, and 12,000 people showed up at her funeral.

So Tex Guinan had it all, from both ends of the Dallas Blonde spectrum. Even though she was a lifetime criminal like Bonnie Parker, she never killed anybody and she only violated laws that eventually the country decided shouldn’t have been laws in the first place. And even though she was a statuesque beauty who stood up for her rights, like Helen Ramsey, there was nothing goody-two-shoes about her. She kissed whomever she wanted to kiss, and she didn’t care who knew it. She once marched with the National Woman’s Party, protesting a law that would have limited women’s work hours. And in her will, all her remaining money went to her dear Irish mother.

One thing that was never known about Tex Guinan is exactly how many times she was married and divorced. Only two marriages are documented, but she was suspected of covering up others, not to mention the ones that she never bothered to formalize. This is an almost universal characteristic of the Dallas Blonde: no one man can satisfy her.

That, then, is the taxonomy of the Dallas Blonde and the historical backdrop against which the events of November 10, 1975, unfolded. On the week leading up to that night, ABC Sports producer Roone Arledge temporarily assigned Andy Sidaris, a former Channel 8 director who had gone on to great fame as the genius behind Wide World of Sports, to fill in for the regular director of Monday Night Football. The opponent was Kansas City. The game at Texas Stadium was close and high-scoring—and long.

Sidaris—a brash, funny, frequently profane Greek from Shreveport—was known for his love of pretty ladies. As the main college football director at ABC, he was the inventor of what came to be called “the honey shot,” which had already made many a college babe famous on campus. He’d even “discovered” a particularly fabulous University of Alabama cheerleader who became the wife of his sideline reporter, Jim Lampley. So when Sidaris took his swivel-chair seat in the remote transmission truck for the Dallas-Kansas City game, it was no surprise to anyone when he barked to his cameramen, “Okay, find the honeys!”

As the cameras panned across the sidelines, lingering on each Cowboys Cheerleader, Sidaris said, “That’s the one! The blonde! She’s having sex with the camera!” Then, throughout the evening, Sidaris would return to this particular babe, who winked, flirted, and posed in one of those defining moments that some claim launched the whole Cowboy Cheerleaders franchise. In fact, that moment may be single-handedly responsible for rescuing the fashion statement of hot pants and Daisy Mae halter ties from what should have been early-’70s oblivion so that, long after every Southwest Airlines flight attendant had burned her orange shorts, the tradition lived on in beer commercials, Maxim magazine, and Hooters restaurants everywhere.

On Tuesday, November 11, 1975, at office watercoolers across America, the conversation was not about the 34-31 final score (the Cowboys lost), but rather: “Did you see that girl? Who was she?”

And here’s the best part: to this day we’re not sure who she was. If you ask people who worked in Tex Schramm’s office at the time, they’ll tell you that the girl was Tami Barber, a pert blonde beauty who was indeed one of the most popular cheerleaders and had a brief acting career of the Love Boat guest-star variety. But the dates don’t match up: Tami Barber didn’t arrive on the scene until two seasons later, after the cheerleaders were already an international phenomenon, and Andy Sidaris went to his grave claiming it was a girl at this particular game in 1975. The official history of the cheerleaders disagrees with Sidaris and ascribes the sea change in the squad’s fortunes to a winking beauty at Super Bowl X. Indeed there was a winking beauty at Super Bowl X—held in Miami in January 1976—but she was a brunette, and that would just be wrong! And, once again, Sidaris disputed this.

But I actually kind of like the fact that we’re not sure which blonde cheerleader launched the myth. Just as the causes of the Trojan War are shrouded in mystery, and the founders of Rome come from a time before history, so the origins of the Dallas Blonde are a fit subject for endless metaphysical speculation, and it will no doubt consume the energies of several generations of the city’s theologians to parse out the best available evidence.

What we can say for sure is this: she came, she conquered, and she was blonde.

Joe Bob Briggs (aka John Bloom) is a former contributing editor to D Magazine. He lives in New York.