The national outlook is less than bullish for MBA programs. Oversupply has triggered a full-bore crisis on some campuses. Demand for the traditional two-year course at most business schools has dropped in the five past years.

Some full-time, on-campus programs have even closed, including the University of Iowa, Wake Forest, Thunderbird, and Virginia Tech. Prospective international students, a lucrative source of revenue, are finding it harder to get U.S. visas under the Trump Administration, while Canada, Australia, and Europe offer easier alternatives.

Heightening competition for U.S. students are online programs, some charging budget-friendly prices, like $12,387 at Texas A&M Corpus Christi. Soon to join the scramble with even cheaper tuition is an Israeli tech firm called Jolt. It’s planning a New York beachhead after registering 2,000 students at other campuses.

But SMU’s Cox School of Business is meeting the challenges and then some, says Dean Matthew B. Myers.

To accommodate a growing student population, the school is planning a major fundraising campaign to erect a new state-of-the-art building and renovate older facilities.

Now marking its 100th year, the school has covered the table with choices. Executive MBAs are down steeply, with fewer companies willing to foot the bill, which runs $122,995 for the 21-month course plus a $2,800 enrollment fee. But the yield from two-year program applicants is up, Myers says. “We’re filling classrooms.” There are 115 full-time two-year students, a gain of 12 from 2014.

The undergraduate BBA program remains vigorous, with the spring 2020 enrollment up 29 percent from 2015. And it continues to draw high achievers. Sunjay Chawla, a 19-year-old freshman from Greenwood, Mississippi, chose SMU Cox over Harvard.

“I wanted to go where I’d be most happy. There are incredible internship opportunities here,” he says, citing everything from private equity firms to professional sports teams.

And although Cox’s online MBA program was a latecomer to the expanding e-universe, the response has been promising, despite the $91,832 price tag. The one-year MBA program has grown from 14 students in 2015 to 55 this year.

And the school is making other advances. Shane Goodwin, associate dean for executive education and graduate programs, says women now make up a third of MBA students, and historically underrepresented minorities now account for 21 percent—“an incredible metric.”

Ever since its launch, the school’s fortunes have been tied to Dallas’ supportive business community.

Myers notes that most of the two-year programs that have closed across the country were located in rural areas, lacking the dynamic regional economy needed to draw applicants or close working relationships with big companies. By contrast, Dallas and Texas have both in spades.

And the proof is in the numbers. About 70 percent of Cox School students come from outside the state, and 70 percent stay and work in Texas or start companies here after they graduate.

Shaky Start

The business school, formerly called the Department of Commerce, Finance and Accounts, advertised secretarial courses as well and was created in 1920 at the urging of the Dallas Chamber of Commerce.

The first class of two men, both with two years of previous college work, graduated in 1922. But the fledgling department almost didn’t make it to its second commencement.

In March 1923, its instructors threatened to resign en masse because of a philosophical and territorial dispute with the Department of Economics, with which it shared some curriculum as well as cramped quarters, according to Journey to Prominence, a history of the Cox school that was published in 2007.

An existential crisis was averted only when Dean E.D. Jennings announced that the two departments would be physically separated in six months. Moreover, he said, the commerce department would pursue “vocational” courses, while the economics department would offer “academic” classes.

The book’s co-author, Thomas E. Barry, a former Cox professor and SMU administrator, said the school had three “foundational” deans from 1920 to 1968. Shaking those foundations was C. Jackson Grayson Jr., a crime reporter turned FBI agent turned academic (Wharton MBA, Harvard Ph.D.) who taught finance at business schools in Europe. It was 1968 when many campuses were roiling with activism.

Grayson embraced quality but also change, doing away with required courses, putting students on decision-making panels, introducing classes in meditation, and transfusing fresh blood into the lecture halls. Among the professors he recruited was Patrick Canavan.

The Yale-educated organizational expert wore jeans and flip flops, replaced his office door with hanging neckties, and used his cassette player to blast Bob Dylan songs like, The Times They Are A-Changin’.

The wildly popular academic was asked—or forced—to resign after an interview he did with SMU’s The Daily Campus newspaper outraged heavy hitters in the Dallas establishment by calling for radical change. The school’s cozy relationship with the business community cut both ways.

In 1971, Grayson took leave at President Nixon’s invitation to become chairman of the U.S. Price Commission. That left Assistant Dean Bobby Lyle, a proponent of the school’s transformation, as acting dean.

He served in the role for 15 months then was named executive dean when Grayson returned. Many reforms were implemented under Lyle’s long-range plan. Barry’s book calls the 1968-75 period among the school’s “most interesting and innovative chapters.”

Ties with the local business community were exponentially strengthened when Dean Albert W. Niemi Jr. arrived in 1997. A former business school dean at the University of Georgia, he was “very deliberate in my first 100 days” in Dallas, Niemi says. “We weren’t telling our story, letting companies in the region know just how good we are. I came face to face with 1,000 executives to let them know how they could help.”

The close-knit relationships that Niemi forged have proven to be enduring. Deep engagement with some of the region’s most successful business executives is a powerful lure for recruiting students.

That was the case with David Brown. He took a circuitous route to the Cox school, majoring in theater, then struggling for years as an actor in New York City, teaching SAT prep classes, and doing web design before landing a job at an Apple store.

The 34-year-old Brown thrived in the retail environment, was made an Apple manager in New York, then in Dallas. He decided to return to school for an MBA and hoped to remain in the region, but with high GMAT scores, he had options.

The chance to take a class on customer engagement from Hal Brierley convinced him to choose SMU. Sitting in on lectures by the innovator who helped design American Airlines’ frequent flyer program (and loyalty initiatives for Hilton, United Airlines, the NFL, and many others) was like learning geometry at the feet of Euclid. Brierley teaches a course on the fundamentals of his field.

He also funded and is actively involved with Cox’s Brierley Institute, the world’s first center devoted to customer engagement. “That was a huge draw, and a differentiating factor for SMU, to be in a class with Hal,” says Brown, who just landed an internship with Siemens and hopes to remain in Dallas after graduating in 2021.

Real-World Impact

The Cox network serves as a magnet for prospective students and provides not only future employees for area concerns but also practical solutions to a range of issues.

When a startup called PICKUP—an Uber-like, last-mile delivery service for furniture and other large items—decided it was time to expand into new markets, CEO Brenda Stoner contacted Cox.

Hattie Tabor, an Accenture vet who runs the school’s M.S. in Business Analytics program, answered the call. Her students determined target cities, then the availability of pickup-owning drivers willing to work at a profitable rate. The team also dissected PICKUP’s data, creating a simplified pricing model, which factored in such things as the prevalence of staircases, typical mileage, and a weighted item count, rather than an aggregate of each.

“The findings were incredibly useful and have been adopted for specific retail partner pricing,” says Stoner, whose clients include Pottery Barn, HomeGoods, and World Market.

Earlier this year, before COVID-19 put the kibosh on large gatherings, school benefactor Edwin L. Cox joined Myers, Miller, SMU President R. Gerald Turner, and others to celebrate the school’s “Texas-sized impact” over the last 100 years.

Looking ahead to the next century, Myers says SMU Cox will continue to work closely with the local business community: “Companies and the city want to know how we can be a better player in their growth by attracting talent for them and establishing the type of quality educational connectivity that makes North Texas a more robust place to learn.”

Images courtesy of SMU.

Gerald Alley

MBA, 1973

The son of a service station owner in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, Gerald Alley says he found the perfect environment at SMU to nurture his budding entrepreneurial ambitions. “SMU was a cocoon in an urban city,” says Alley, president and CEO of Arlington construction firm Con-Real. “Once you left campus, you were back in the city.” One of a handful of African-American students at the time, Alley says he didn’t feel singled out in any way. “Professors made the assumption that if you could get in, you could do the work.”

He says he especially appreciated hearing the perspectives of practitioners who served as guest lecturers. “One day the professors taught you the theory, the next day Craig Hall of HALL Group would be explaining how they actually did things. One told us how he learned from each of his failures. That, to me, was a real eye-opener. “ Another guest speaker who stood out: Ray Hunt. “He took an old railroad yard and created a new development with a first-class hotel,” Alley says. “At the time, Kennedy’s assassination was still a stain on Dallas’ image. When asked why he was building Reunion Tower with a ball on top, Hunt said he hoped it would help create a new symbol, a new image for the city.”

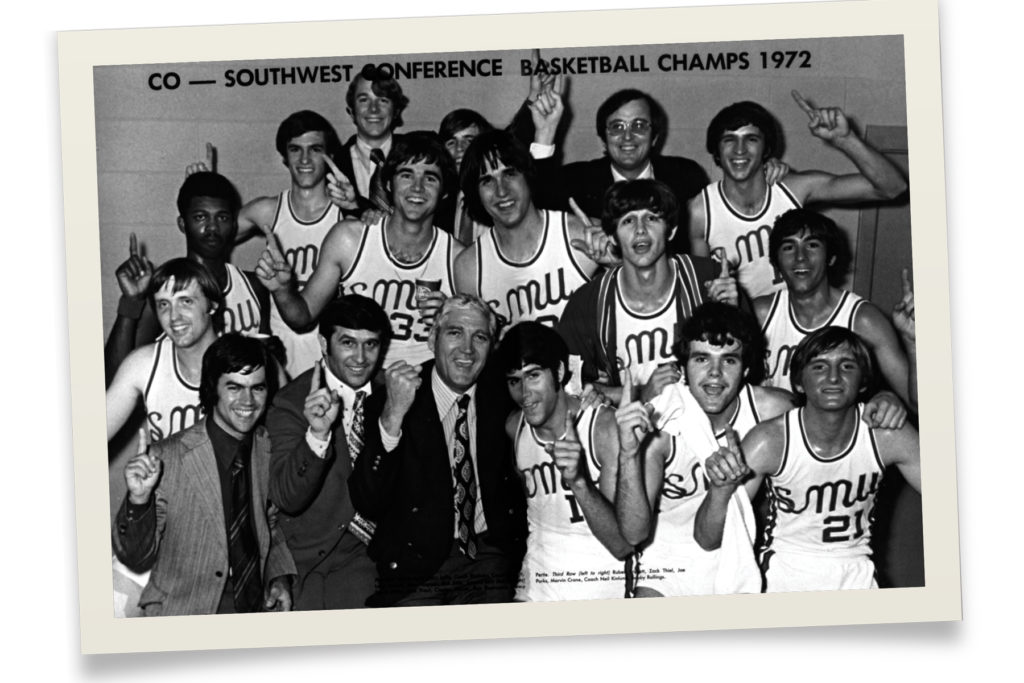

Bobby Lyle

Acting Dean, 1971-1973

Bobby Lyle, who made his fortune in energy, is a modern-day Renaissance Man—engineer, educator, business executive, philanthropist, and community leader. But he also served as an acting dean and executive dean at SMU’s business school during transformative years. Dean C. Jackson Grayson Jr. asked Lyle to shape what became the first strategic plan. “Grayson was a dissident dean, an outlier,” Lyle says. “He knew that Columbia or Dartmouth or Wharton were like huge battleships, hard to turn around. But SMU’s business school was like a little speedboat. It was a fun time; we pushed the envelope.” An early mission was to create a new type of MBA class. “One of the first things I did was recruit the first black MBA students and more women in the business program.”

David Miller

BBA, 1972 | MBA, 1973

Don Jackson, a revered professor of banking, pulled a basketball player named David Miller aside and changed his life. Miller was in Jackson’s finance class and sat in the back of the room with the other jocks, but scored well on a test. “Look,” Jackson told him. “You have potential to do things in life. But you’ve got to get your butt from the back row and participate in class.” Miller heeded the advice. The first in his family to graduate college, Miller followed his undergraduate degree in business administration by earning an MBA at SMU. He pursued a career in banking and, later, energy. Last year, Miller and his wife made the biggest single donation in Cox School history—$50 million. It was payback. “I attended SMU for five years,” Miller says, “and never paid a dime.”

Billie Ida Williamson

BBA, 1974

Billie Ida Williamson, a high school valedictorian from Fort Scott, Kansas, somehow landed a one-on-one meeting with Dean C. Jackson Grayson Jr. “He was very easy to talk with and was excited about what was happening at the business school, especially for women, she recalls.” Partially a result of that encounter, Williamson applied only to SMU.

The young Kansan thrived in the school’s accounting program. She also served as student body treasurer and was named homecoming queen. During senior year, she confided to a professor that she couldn’t decide between two job offers. “I had a big spreadsheet of pros and cons,” but Michael “Mick” McGill, a professor of organizational behavior, told her, “OK. We’re going to flip a coin.”

Ernst & Ernst (now EY) would be heads; the other firm, tails, he said. She balked, saying, “We can’t make an important decision like this!” McGill urged her to play along. “I flipped the coin, and it came out to be the other firm. The words out of my mouth were, ‘I don’t want to work there.’ He used it as a teaching moment, telling me, ‘That’s why your gut feeling is so important.’” Williamson spent 33 years with EY and was one of the first women in the international accounting firm to be named partner.