The pandemic put an unprecedented strain on the healthcare industry, especially in regions hardest hit by COVID-19 infections. But just as the virus inundated some areas with patients, patient load in other regions experienced at all-time lows. North Texas never saw a major spike in patients, leaving many hospitals relatively empty and physicians out of work.

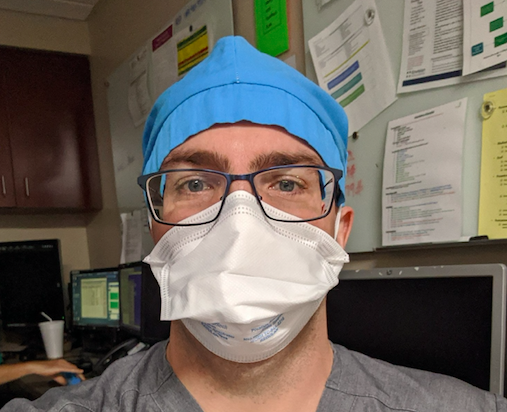

Medical City McKinney emergency physician Dr. Mike O’Neal was one of the local doctors whose hours were decreasing, so he made the bold choice to work in two COVID-19 hot spots, New Jersey and the Rio Grande Valley. O’Neal felt the pull to help where he could and was looking to stay busy and provide for his family. “I’m kind of sitting there twiddling my thumbs with a little bit of cabin fever,” he says.

Through his physicians group, he took a position with Robert Wood Johnson Barnabas Health System- Hamilton in Hamilton, New Jersey, which he found to be about the size of his home hospital in McKinney. It was about an hour outside of New York and was not as overwhelmed as many hospitals there, but things were still busier than usual. For five weeks in April and May, O’Neal worked the night shift as part of the rapid response team, which steps in when a patient stops breathing. This team responds to “code blue,” which is a cardiac or respiratory arrest. He would spend his nights literally saving lives.

“It wasn’t the scary place New York was at the time; they weren’t quite as hammered,” he says. But his emergency skills were put to the test, as the hospital was still experiencing more codes than usual. He was part of a team that included an intensive care unit nurse, a respiratory therapist, and other technicians who would quickly respond to emergencies. While in New Jersey, there would often be multiple incidents that required the rapid response teams, pulling team members onto other codes. One night, O’Neal says, there were three simultaneous code blues.

He remembers getting a tour of the hospital in New Jersey when he first arrived, and the guide pointing out a set of windows that had been recently frosted so that one couldn’t see out. The hospital modified the windows because the facility had doubled the refrigeration unit’s size on its morgue to deal with the increased deaths due to COVID-19. They were forced to store the bodies until the funeral homes could take them.

There might be several days between code blues in McKinney, though there may be several rapid response moments within a shift. New Jersey was a different story. “I think there is was one night [in New Jersey) where I had zero code blues and zero rapid responses, and that was super rare,” O’Neal says. Most other nights had five or so rapid response moments and three or four code blues per night. During many of these shifts, he found himself rushing between floors, trying to respond to the codes or preempt them when possible. “At times, we would move intubated patients back down to the emergency room, as it was the best area to care for critically ill COVID-19 patients, while we waited for an ICU bed to open.”

After weeks in New Jersey, he returned to North Texas, but numbers were still down, so he took a shorter trip to Rio Grande Regional Hospital in McAllen, near Mexico’s border. This was one of the country’s hardest-hit areas, with large uninsured populations who also suffer from comorbidities that increase the disease’s deadliness. O’Neal spent just three days there, but there were three code blues in the hour he was finishing his credentialing. There were another couple codes the rest of the day, four to five in his next shift and two or three the next shift. In the hallways of the hospital, overflow patients laid face down on ventilators due to overflow.

In New Jersey, several floors and wings of the hospital had been turned into COVID-19 units, and in McAllen, he felt like nearly the entire hospital was treating COVID-19 patients. The severity of the disease, and its impact on using hospital resources, stuck with O’Neal. “The patients who got sick with COVID, even the ones who survived, were hospitalized for an incredibly long period. If a patient was placed on a ventilator, we assumed that patient would be on the ventilator for two-plus weeks. And that puts incredible strains on systems,” he says.

O’Neal was well aware of the risks he was taking, but as a young and otherwise healthy physician, chances were likely he would be fine. And he felt a duty as a physician. “My Mother wasn’t real happy with my decision but said that she kind of expected it. What’s the point of being a doctor if you aren’t going to go respond to these situations?”