Much of the historic Freedman’s town of Tenth Street has been lost to time and demolition. Even a Landmark designation from the city three decades ago did little to stop the destruction of its homes in this pocket just east of Interstate 35E, in Oak Cliff.

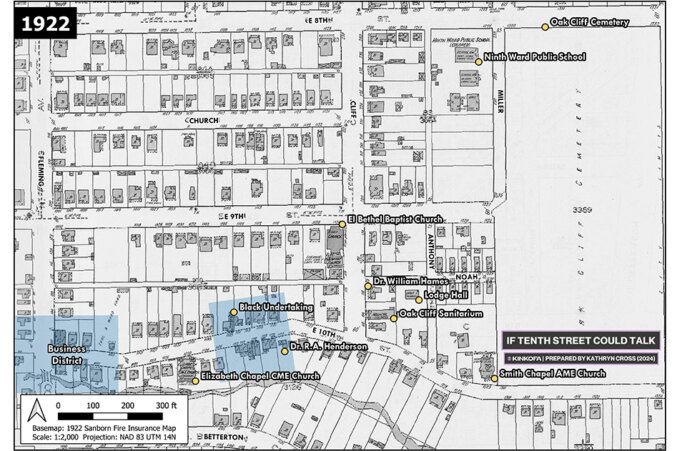

Piecing together that lost history is daunting. But SMU archaeologist and doctoral student Katie Cross is using technology to combine the stories and history of Tenth Street with geographic information systems (GIS) to tell the community’s story. It’s part of a collaborative effort called “If Tenth Street Could Talk,” which includes kinkofa, a technology company that provides resources for Black families to document and preserve their stories. (More of Cross’ work can be found here.)

Tameshia Rudd-Ridge and Jourdan Brunson, the co-founders of kinkofa, worked with genealogist Dolores Rodgers to record oral histories, digitize photos, and research genealogy to create a digital museum of Tenth Street. They’re also collaborating with Remembering Black Dallas, the Dallas Public Library, and the Tenth Street Residential Association. The work is possible thanks to a grant from the Library of Congress.

“I was combing through city directories and census data. Sanborn maps,” Cross says. “I was looking at aerial imagery, and then putting it into one place. I was georeferencing them, which is putting them on top of where they are in the real world on a map.”

They can also attach to the map the oral histories collected by kinkofa and other organizations like Remembering Black Dallas.

“We can look at how infrastructure impacted the community,” she says. “And when you put it all together, it shows this narrative of a vibrant neighborhood despite the infrastructure that disrupted it.”

Present-day Tenth Street is bounded by Interstate 35, East Eighth Street, and Clarendon Drive at the eastern edge of Oak Cliff, not far from the Dallas Zoo. But the community began in the 1880s, south of the Trinity River, as formerly enslaved people settled and began buying lots and homes. By the turn of the century, those families had created a community with churches, a school, and small businesses. By the 1950s, nearly 2,000 residents lived here. At one point, it had a hospital whose doctor lived next door.

Jim Crow-era policies began to change that community, separating blocks by the race of homeowners. Black homeowners were sometimes forced to literally move their homes to nearby blocks because they were located on a “White” block. Redlining and disinvestment by the city followed. In the 1960s, I-35 was routed through the neighborhood, cutting it off from the rest of Oak Cliff while demolishing neighborhood businesses. In 2010, the city passed an ordinance that allowed homes in Landmark Districts to be torn down if they were smaller than 3,000 square feet. Nearly all the homes in Tenth Street fit that bill. Fourteen years later, the Dallas City Council voted to repeal the ordinance after years of demolitions.

The area’s last commercial building stands vacant and boarded up. At one point, Simpson’s Corner Store was one of 40 businesses in the neighborhood. Greater El Bethel Missionary Baptist Church is still holding Sunday worship, but it’s the only church remaining out of the eight that were once present in the neighborhood.

Rudd-Ridge learned firsthand how history disappears when she began researching her own family. When she found that jazz trumpeter Clora Bryant was a cousin of her great grandmother, she began to search for her home. She looked on Betterton Circle, but found an access road at the edge of a highway instead.

“Literally the highway is where my family home was supposed to be,” she says. She related her frustrations while on Remembering Black Dallas bus trip with the late George Keaton and Tenth Street resident Larry Johnson not long after.

“They said, ‘Well, what are you going to do about it?’” she says.

That was almost three years ago. Since then, Rudd-Ridge and Brunson have worked to document the history of the neighborhood—even when longtime residents sometimes question whether their stories are important.

“Your lived experience is valuable,” Rudd-Ridge says. “The every day is really what makes a people’s history.”

Brunson said that similar work the organization has done in Tulsa found that people are sometimes unaware of their history. They’ve found that to be true in Tenth Street, too.

“They don’t know the significance of the heyday of the community, or even the current issues they’re battling,” he says.

Cross says she hopes that the work done in Tenth Street will force a change in what is considered worthy of preservation.

“Historic protections aren’t perfect,” she says. “They do not stop destruction. We need to rethink how we do historic preservation.”

A broader understanding of historical places and why they’re important will help. Rudd-Ridge says she hopes Tenth Street residents now have the city’s attention, and that there is momentum to change what happens in the community. Eventually, they’d like to see the neighborhood showcased as one of the few intact Freedman’s towns in the state, and cement it as a Black cultural destination.

“Our goal is to keep applying positive pressure,” she says.

In the meantime, they’ll continue to help people visualize the history they can’t see, one map and story at a time.

Author