A new study of the air quality along the Singleton corridor in West Dallas contains few surprises for nearby residents. Nevertheless, local leaders said Wednesday that the results are why the city should eliminate the industrial polluters that operate alongside the neighborhoods that flank Singleton Boulevard.

The area is dotted with heavy industry. The busy Singleton Boulevard and a railroad transect the community, which is bordered by the Trinity River and Interstate 30.

Similar to a study conducted in the Joppa community of southeast Dallas last year, researchers at Texas A&M used air monitor data from SharedAirDFW.com and self-reported survey results from residents. The community group Singleton United/Unidos, which represents those who live closest to the factories that produce things like shingles and concrete, assisted in collecting the responses. The effort was a collaboration between the community and the environmental activism nonprofit Downwinders at Risk.

The results were even worse than in Joppa, where 18 percent of its residents report being diagnosed with asthma at some point in their lives. In West Dallas, that number climbed to 34 percent, well above the 7 percent average for Dallas-Fort Worth.

While the monitor compiled data, volunteers surveyed community members. They reached 38 percent of the estimated 227 neighborhood households.

“We have the stats, perceptions, air monitor data, reported symptoms, and we put together these results, but the reality is that in our neighborhood, we know the harm,” says Janie Cisneros, a leader with Singleton United/Unidos. “We know the harm because we experience it. We believe we are being harmed and that pollution is harming us, and we just saw data that says it is.”

Researchers at A&M focused on one particular pollutant: particulate matter 2.5, or PM 2.5, microscopic pollutants that are about 100 times smaller than a human hair. They can be absorbed into the bloodstream, and long-term exposure is linked to a variety of neurological, cardiac, and respiratory issues.

One SharedAirDFW monitor, which was built by UT Dallas researchers, was placed about 600 feet northwest of the GAF shingle factory. It recorded 35 occasions when the plant’s emissions exceeded the Environmental Protection Agency’s 24-hour particulate matter standard. The closest EPA monitor is on Hinton Street, almost 5 miles away in the Medical District. It recorded no violations, which the community argues is proof that it isn’t close enough to accurately measure the pollutants in the neighborhood’s air.

Dr. Natalie Johnson, a toxicologist at Texas A&M, says that disparity shows that it’s important to collect air quality data within the neighborhood and not rely on the nearest regulatory monitor.

“On average the Singleton corridor daily PM burden was up to 11 times higher compared to the county average,” Johnson said. “The range is quite high going even to kind of visibly seen levels of pollution in some cases during those summer months.”

Because PM 2.5 travels into the bloodstream, researchers and advocates say all exposure poses health risks.

“There are no safe levels of particular matter 2.5 PM—there’s nothing safe about it,” said Caleb Roberts, the executive director of Downwinders at Risk. “There are allowable levels, which is where the government says, ‘We will allow businesses to pollute to this extent,’” but really, there’s no part of this that is safe for you to breathe and that’s safe for communities to be around. We’re talking about degrees of impact.”

The impacts along the Singleton corridor are stark. Forty-two residents reported being diagnosed with a respiratory disease within the last year, and 86 percent said their respiratory symptoms had gotten worse since they moved to West Dallas.

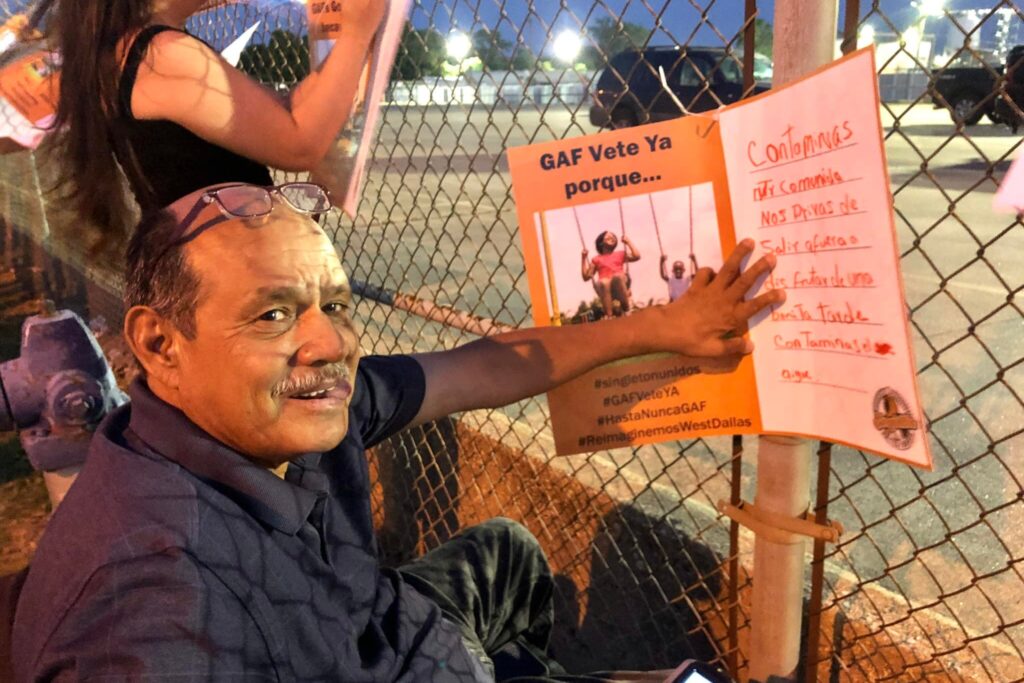

The results, Cisneros said, were unsurprising, but she also felt the data validated what she and her neighbors have been saying all along. They are in their third year of a protracted fight to move the GAF factory out of the neighborhood.

Singleton United/Unidos two years ago published a white paper explaining the hazards emanating from the factory. The company announced not long after that it would voluntarily relocate, but would need until 2029 to completely wind down operations. The community has demanded an earlier move-out date.

More recently, Cisneros sued the city after she was not allowed to file to start the amortization process, which is used by cities to force a business to move away from an area if it no longer conforms with the zoning or land uses around it. The city’s attorneys cite changes in state law that impacted how Dallas can handle the amortization as the reason the city refused Cisneros’ application.

But in the case of West Dallas, the pollution detailed in the report is only the latest indignity visited upon the area. In the 1980s and 1990s, the community fought to remove RSR Corp.’s lead smelting factory at Westmorland and Singleton. It sat as an EPA Superfund site until being excavated and redeveloped in 1995. Even two decades later, some residents reported finding lingering debris on their property. The plant may be gone, but in this study, 24 percent of the respondents said they had experienced childhood lead poisoning.

“Victims of lead poisoning are more susceptible to all kinds of environmental insults, including air pollution, especially in the amounts documented in this neighborhood,” Johnson said.

But lead and PM 2.5 aren’t the only toxins Singleton corridor residents have encountered. Between 1967 and 1992, almost 400,000 tons of asbestos-contaminated vermiculite ore was trucked in to the West Dallas W.R. Grace factory before it was shut down. The EPA finally cleaned up the land in 2001, only for it to be replaced by a concrete batch plant. In 2022, a second survey of land around the plant (including land belonging to homeowners and businesses) found additional asbestos contamination.

Roberts calls the issue environmental racism. He points to national statistics that show that communities of color are three times as likely to be exposed to noise and air pollution, and two-thirds more likely to be exposed to toxic waste.

“When we look at the aerial view of the Singleton corridor in West Dallas, you can see how some communities are put in places that are closer to polluters,” he said. “We understand the ways to get industry away for some people, but for others, it doesn’t seem like it has ever been a priority for the city.”

Roberts points to the EPA’s environmental justice screening tool, which indicates that the particulate matter exposure along the Singleton Corridor is among the worst in the U.S., as is exposure to cancer-creating toxins and respiratory toxins.

“We’re talking about a long history of things here and an at-risk population who are now susceptible to all kinds of health impacts,” he said.

Armed with data, Joppa residents were able to argue that the city should not renew the permit for a concrete batch plant there. Cisneros is hopeful that the same successes will come to her community.

“What can we do about it?” she said. “Fight to stop the pollution, which is what we’ve been trying to do. We have opportunities to do that.”

One of the ways to stop polluters, she says, is a zoning case involving GAF that will allow residents to voice their concerns. GAF has applied to change from the industrial zoning currently assigned to the 26.5-acre tract of land upon which it sits on to zoning for mixed-use development like retail, offices, hotels, or even apartments. While a zoning hearing has not yet been set, Cisneros said the hearing process will allow her neighbors to explain why operations should cease at the plant before 2029.

“We know that the longer that GAF stays in the community, the sicker we’re going to get,” she said. “We’re not going to get any healthier.”

Author