It’s Friday night on Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard in South Dallas. Propped against a brick wall outside a liquor store next to the Forest Theater, near the intersection of Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard and S.M. Wright Freeway, a 24-year-old Hispanic girl holds a beer down by her waist as she takes a drag from a clove cigarette. Her name is Laurisa Galvan. She’s 5-foot-1, with long, gleaming black hair that comes halfway down her back. Fresh-faced and pretty, she’s wearing a tank top and jeans, and, yet, you can tell she’s trying to fit in.

Galvan is not who you’d expect to see hanging out on this corner, a place known for its drug dealers and pimps, a place where police often troll but officers rarely stop and get out of their squad cars. But for almost two years, she has loitered here and at a few other strategically chosen spots nearby. She has gotten to know some of the regulars. She calls the store owners by name and chats them up when she buys her nightly beer. She has found that a lot of the other people hanging out here are felons on parole, and almost all share financial hardship. Galvan, on the other hand, doesn’t do drugs, and she doesn’t have a record. She’s not even from South Dallas. The recent graduate of the University of New Mexico grew up in a middle-class Hispanic family in New Mexico and moved to Dallas after graduation. She found this neighborhood when she was still a photography student and traveled with her camera to Dallas on spring break, looking for a subject. She ended up here when she asked someone to point her to the city’s most dangerous neighborhood.

“They are always the most interesting,” Galvan says.

“If you ever need anything, I’m here,” the officer said, handing her his card. “Be careful.”

The irony is that perhaps the most dangerous thing that could have happened to Galvan was speaking to the cop. When the young photographer first began hanging around these spots, many of the regulars thought she might be an undercover officer. It took time to build trust. She left her camera in her car and spent hours doing nothing, just hanging out. Occasionally, she was teased or gently harassed. Only a few times she felt genuinely threatened, when a certain look came over someone’s eyes and she remembered she was a pretty, defenseless 24-year-old.

“I’d just go to my car, lock the doors, and call it a night,” she says.

The Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard gadflies have little to gain from getting their pictures taken, and even more to lose. It is not surprising it took Galvan so long to find subjects. Many of the people here live in constant fear of violating paroles. Others are concerned about how pictures can objectify or mischaracterize a community. Once, when Galvan was out on the street, an older white man with a camera was walking around taking photos. He tried to explain that he was working on a project about urbanism, but the shouting, swearing, and threats that were hurled his way sent the man scurrying back to his car. Galvan says he is the only other person with a camera she’s seen out here.

Galvan’s first photo came at a car wash. A man in a tank top, with a long, gold necklace and a high-top, fade haircut, rolled up in a green Caprice Classic with huge rims. Growing up in Española, New Mexico, known as the “Lowrider Capital of the World,” Galvan’s brother had cruised around with friends.

“My brother has a Caprice Classic,” she told him. “Can I take a picture of it?“

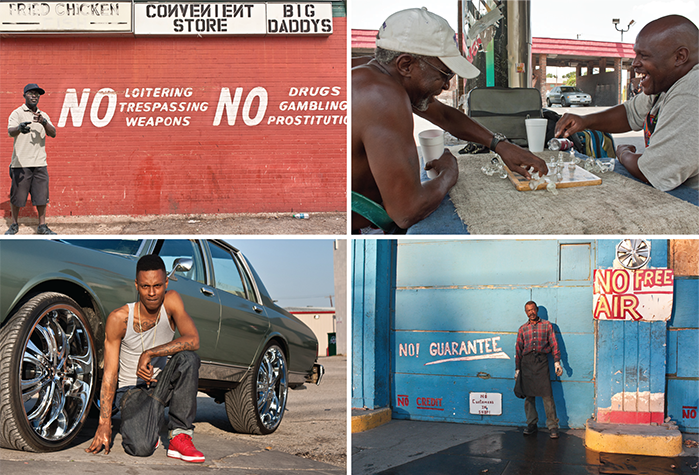

Over time, more and more people in the neighborhood began to let Galvan take their pictures. At first, they were just candid shots: men hanging out, smoking cigarettes next to No Loitering signs; giggling children posing in trash-strewn vacant lots; a woman in a too-tiny tank top and 5-inch wedges propped up against the Forest Theater facade, catching glances from a few men straggling yards away. Eventually, her subjects let her get closer. Galvan has photographed chess matches and craps games; women posing on the hoods of souped-up purple cars; an old preacher wearing a bright grin, his crooked body echoing the slumping, tumbledown, shotgun church behind him.

She has also managed to catch glimpses of more nefarious dealings, such as one photograph of an electric stove cluttered with plates of half-cooked white powder and razor blades. But in this image, like all of her photographs of the neighborhood, what is most striking is the blameless tone. Galvan’s lens doesn’t sensationalize, and while many of these scenes can’t help but resonate with a powerful social critique—of the clear urban blight and political neglect that frames Dallas poverty—they are presented as a subculture simply captured by an unjudging eye. Viewed in a series, her photographs begin to speak to an inextricable connection between urban architecture and personal artifice, of pain and pride, social and political disenfranchisement, personal demons and perseverance.

Some of Galvan’s best photos are portraits. In one, a shirtless man shows off his tattoo of the Dallas skyline that stretches across his chest. In another, the picture is dominated by a close-up shot of a wide, smiling mouth filled entirely of gold and jeweled teeth. Even candid shots that seem hastily framed offer a wealth of meaning. In one such photo, a beautiful woman who looks to be in her early 30s poses in a crisp, white pantsuit; open-toed heels; and white, wraparound sunglasses. She grasps a small brown paper bag in her hand and stands in an empty lot. The front end of a beat-up pickup truck peeks in from the side of the frame, and the blistered, concrete parking lot she stands on bleeds into an unpainted, potholed street. At the far rear of the image, a forlorn, straggly, leafless tree looks like a black ink squiggle against a fading, white brick building.

Galvan’s project has never had a definitive aim. It’s difficult to focus on any single subject (when she tried to find the man with the gold teeth after the image was published, someone told her he was either back in jail or dead). And even though her work has won her awards and the images were published in the UK’s Guardian newspaper, the young photographer says she just wants to spend her time ingratiating herself deeper into the South Dallas community. She’s not sure what shape it will all take when she’s done—or even if it’s something that she could ever actually finish. For now, though, Galvan has already accomplished something rare. With an outsider’s eye, Galvan found a way to give her overlooked subjects real voice.