Every year at Sundance, there is a mob-scene screening just like this one, the clusterf–k, to employ festival parlance, the movie premiere that, for some reason or another, everyone—the talent agents and distribution executives and entertainment journalists and even the vacationing ski bunnies—decides they must attend, or otherwise they are nobody in the film industry worth taking seriously.

The buzz on Ain’t Them Bodies Saints, a Texas-set tale of outlaw love starring Rooney Mara (The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo), Casey Affleck (Gone Baby Gone), and Ben Foster (The Messenger), has been mounting steadily in recent days. The New York Times has reported of “whispers from festival staffers that it could be this year’s version of Beasts of the Southern Wild—a critical darling that blossoms into an indie hit.”

The screening is set for 12:15 pm, at the 1,269-seat Eccles Center, the festival’s largest venue. Ninety minutes prior, the bottom level of the facility is packed with two dozen or so cameramen and reporters, all squeezed together in a roped-off pen, waiting for the stars to arrive. Mara turns up first, a bird-thin little thing, all in black and baring just a hint of midriff. She wears a solemn expression that, if not quite pained, certainly hints at some sort of emotional duress. Affleck follows a few minutes later, a vision in olive-drab khaki, looking like he got lost on his way to a day job at The Home Depot. Next comes Foster, though before anyone can ask him where he found that scoop-necked, formfitting sweater that shows off his perfectly manscaped chest hair, he breezes right into a VIPs-only green room.

Yet one of these things on the press line is not like the others: his name is David Lowery, the 32-year-old Dallas man who wrote and directed Ain’t Them Bodies Saints. “I wanted to make a film like an old folk song Bob Dylan might have covered,” he tells one of his interlocutors, before moving forward three inches, where another microphone is jammed into his face and the very same questions are asked of him again.

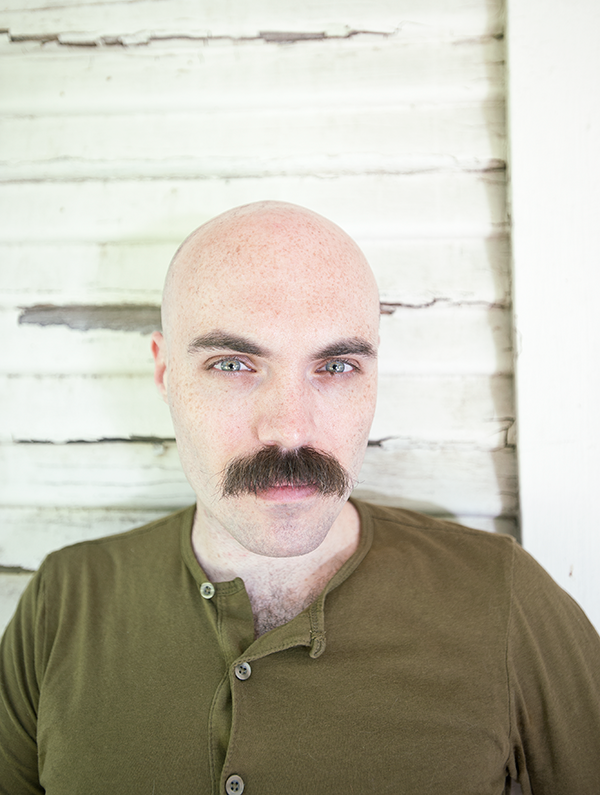

Lowery wears the uniform of the cooler-than-thou indie filmmaker, a vintage brown blazer over an untucked black shirt, black jeans, and black boots. With his bald pate and facial scruff, he’s got the look down, too. But he also has the earnest, sweetly voluble manner of an exceptionally bright teenager; find a point of conversation you agree on, and his eyes light up, and he can’t stop talking. Nor does he seem to have much in the way of ego: he will praise his actors, his producers, his agents, other directors whose films are competing against his at Sundance—but he ritually brushes aside any credit that might be extended to him.

You’d certainly never guess from first meeting him that he might just be the most important filmmaker ever to emerge from North Texas.

The clock strikes noon. One of the publicists shouts, “Sorry, no more interviews,” and whisks Lowery, Affleck, and Mara into the green room. Up a half-flight of stairs, inside the auditorium, dozens of moviegoers skulk along the aisles, searching for a seat. There are representatives from virtually every independent film distributor in the country here, and influential critics and bloggers. The fact that thus far, four days into the festival, no titles have broken out only heightens the sense of excitement: this must be the one we’ve been waiting for.

Lowery takes the stage, makes his way through a soft-spoken introduction. The lights dim. A title card appears on the screen: This Was in Texas.

The buzziest screening of the Sundance Film Festival has finally commenced. The city of Dallas’ great hope—of a director around whom a viable, artificially ambitious filmmaking community on par with Austin’s might be built—is about to be put to the test.

In the next 105 minutes, David Lowery’s career will be made or broken.

•••

The history of filmmaking in Dallas is—how to put this politely?—not entirely a storied one. In the 1950s and ’60s, a string of quickie B-pictures with titles like The Giant Gila Monster were shot in the region. In the 1970s, the television show Dallas (partly filmed in its title city) seemed to inspire a brief boom in production—Silkwood and RoboCop were subsequently filmed in town. In the 1980s and ’90s, Oliver Stone took a fancy to the city, shooting Talk Radio, Born on the Fourth of July, and JFK here.

But for the most of the past quarter-century, Dallas has been better known for commercials, middling television series, and straight-to-DVD horror flicks—work that paid the bills for all involved but didn’t exactly capture the spirit and soul of the place. The most celebrated homegrown talents, whether writer-director Robert Benton (Kramer vs. Kramer) or Luke and Owen Wilson, usually ended up moving away to Hollywood or New York. In 2004, a former software engineer named Shane Carruth premiered a strange and captivating time-travel thriller called Primer. The film won the Grand Jury Prize that year at Sundance and marked its writer-director as the most promising local talent in eons. But after years spent trying to get another project off the ground, Carruth seemed to disappear completely.

Not that any of this would be especially ignominious or unusual—indeed, even at its most commerce-minded, the Dallas filmmaking community is still vastly more impressive than ones in similar-sized cities like Phoenix or Indianapolis. But at the same time that new episodes of Walker, Texas Ranger were being made in Dallas, the city of Austin was turning into an unlikely hotbed—a place of art and commerce. Richard Linklater and Robert Rodriguez famously put the capital city on the cinematic map in the early 1990s, with Slacker and El Mariachi, respectively. Quentin Tarantino adopted Austin as a second home, and went on to shoot his 2007 thriller Death Proof there. Film festivals like South by Southwest and Fantastic Fest started generating national attention. A second generation of critically acclaimed writer-directors, including Jay and Mark Duplass (Cyrus) and Jeff Nichols (Take Shelter), began to rise up.

Pop-culturally speaking, Austin mattered to the world at large. Dallas—well, we did have Barney and Friends shooting in Las Colinas and Carrollton for 20 years.

Enter David Lowery, the oldest of nine children, who moved with his family to Irving when he was 7, after his dad got a job teaching theology at the University of Dallas. Just out of Irving High School, he knew only that he loved movies and might one day want to make them. Yet Dallas wasn’t Austin. Indies weren’t being shot regularly on his street corner. He didn’t know anyone who had attended film school. So he embarked upon a self-education, watching hundreds of films. With no prior on-set experience, he decided to write and direct his own movie, at the ripe old age of 19.

These days, Lowery disavows that first effort, titled Lullaby. (It played at a couple of area festivals in 2000 and 2001, but the director says he has no intention of ever letting anyone see it again.) But one of the people who turned up on the set of the film offering to help was a twentysomething from Fort Worth named James Johnston. A few years later, Lowery and Johnston met Yen Tan, a Malaysian immigrant and copywriter at Neiman Marcus, and Nick Prendergast, a Dallas-based photographer. The four of them collaborated on an omnibus of short films, titled Deadroom, which was accepted by South by Southwest in 2006. Toby Halbrooks, another budding filmmaker and writer and a former member of The Polyphonic Spree, met Lowery on the set of 2008’s Blood on the Highway, a locally shot horror-comedy film. Halbrooks soon entered the circle, too. Under the radar, and far outside of Austin, a creative community was growing.

“The truth is there was something special going on,” Halbrooks says. “In my neighborhood, all my best friends and people that I knew were doing something special culturally that people are recognizing right now, like St. Vincent—Annie Clark—and my friend Ben Curtis from School of Seven Bells. It’s like, ‘Whoa, what was happening in Forest Meadow?’ ”

Lowery’s first breakthrough came with St. Nick, produced by Johnston, Halbrooks, and another friend, Adam Donaghey. Shot for $12,000 in Fort Worth in 2008, it follows two young children (played by real-life siblings Tucker and Savanna Sears) who have either run away from or been abandoned by their guardians. The film struck a gorgeous balance. It’s clearly inspired by the mythopoetic dream-making of Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven, but it also revealed Lowery’s gift for crafting tight, old-fashioned narratives. Sundance turned it down, but South by Southwest said yes, and a couple of discerning critics took notice. (St. Nick still isn’t on DVD, though Lowery expects that it will finally be available later this year.)

That’s when Dallas nearly lost yet another promising talent to Hollywood. Years earlier, Lowery had sold a television pilot script to CBS in Los Angeles. Nothing came of that show, but Halbrooks was also interested in television, and the two decided to move to Los Angeles and try their hands at scriptwriting.

For a while it even looked as if one of their pilots might get picked up by the Epix channel. Meanwhile, their agent kept sending them out on interviews for staff writing jobs on series—potentially very lucrative work for two guys who had been scraping by as starving artists.

“If I had stayed there and really worked hard, I probably could have gotten one of those jobs,” Lowery says. “I didn’t stick around because I realized I didn’t want that.”

Instead, he returned to Dallas and filmed an arresting 16-minute short film called Pioneer, which played at Sundance in 2011. On the strength of a work-in-progress screenplay version of Ain’t Them Bodies Saints, Johnston and Halbrooks were invited to Sundance’s Creative Producing Lab, where independent projects are developed in conjunction with established industry professionals. A few months after that, Lowery was accepted into the equivalent lab for screenwriters. At the 2012 Sundance Film Festival, the team signed with Craig Kestel, an agent with William Morris Endeavor. Kestel passed the script to Rooney Mara, then just Oscar-nominated for The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo—an actress whom everyone was watching to see what she would do next.

“I read his script, and it was everything I was looking for,” Mara says. “Everything—the landscape, the time period, the relationships—I loved the script so much. And I really loved his short film, and then when I sat down with him, he was just so passionate, and he knew exactly what he wanted to do.”

Casey Affleck and Ben Foster soon came aboard, further raising the financial stakes. (Lowery prefers not to discuss the budget, though most estimates place it in the $3-million to $4-million range.) They would have a month in Louisiana (and a few days in Texas) to shoot the film in the summer—which required a little creative scrambling, considering that the story originally took place in the winter—and then just a few more months in the editing room if they hoped to make the deadline for Sundance.

Word came that they had been accepted to the festival just before Thanksgiving—along with word that the community they’d been building from the ground up was finally earning wider recognition. Yen Tan also earned a Sundance berth with Pit Stop, a gay romance that Lowery co-wrote and was produced by Johnston, Eric Steele (one of the co-owners of The Texas Theatre in Oak Cliff), and Kelly Williams (an Austin-based programmer for Fort Worth’s Lone Star International Film Festival). Shane Carruth finally re-emerged with Upstream Color, a hallucinatory Dallas-shot thriller that Lowery co-edited just prior to shooting his own film, and on which Halbrooks served as co-producer. (Pit Stop played in the non-competitive NEXT section of the festival, whereas Upstream Color was in the Dramatic Competition alongside Saints.)

“He saved my life, big time,” says Carruth, who only met Lowery just before he started shooting Upstream Color. “I had this idea that I would edit concurrently to shooting my film—but I was sleeping 90 minutes a night, and it was not happening. David got free and he came on, and it’s the luckiest thing I’ve ever seen in my life. He was perfectly, without ego, willing to do whatever to get it done.”

Carruth adds, “I didn’t really know the filmmaking community in Dallas. I’m shocked that I met those guys, and now we’re all here at Sundance.”

•••

It is late afternoon on Martin Luther King Jr. Day, and the traffic on the road out of Park City is monstrous. David Lowery is starting to worry that he might not make it in time to introduce the second screening of Ain’t Them Bodies Saints, down in Salt Lake City. Their rental SUV is being driven by Halbrooks. Johnston is riding shotgun. Tagging along to watch the movie is Ryan Coogler, a writer-director Lowery met in the Sundance Labs, here with a drama called Fruitvale. If there’s any sense of competition among these men, both up for the festival’s Grand Jury Prize, you wouldn’t know it. Shortly after Fruitvale first screened on Saturday night, Lowery sent out a tweet saying the film left him in tears.

A day has passed since the premiere of Ain’t Them Bodies Saints, and if the film didn’t exactly set off an all-night, over-the-top bidding war, it is nonetheless very much “in play.” Word is that IFC Films, Roadside Attractions, and Magnolia Pictures—all among the most-established indie distributors in the business—are interested.

The movie—which will open in Dallas theatrically on August 23—is not likely to be confused with a mainstream crime thriller along the lines of Out of Sight or True Romance. Mara plays Ruth Guthrie, a young mother whose lover (Affleck) escapes from prison and attempts to elude a manhunt so that he can reunite with her. (Foster plays the town police officer who carries a torch for Ruth.) The story unfolds in Meridian, Texas—judging by the cars on the street, it might be the 1970s; judging by the dreamlike images, it might be 50 or even 100 years ago. The ostensible action sequences—the prison break, for instance—mostly happen off-camera, as Lowery instead focuses on long, moodily lit dialogue exchanges between the characters.

Sitting in the backseat of the SUV heading to Salt Lake City, Lowery looks at once hyper-alert and exhausted, like a guy who’s been coasting on either Red Bull or adrenaline or both. Did he personally go online to read the scores of blog and Twitter posts that assessed the film after its first screening?

“Yeah, I’m a glutton for a punishment,” he says.

But most of them were favorable, right?

“That’s lucky that they were mostly good, but there was this one New York Post review—” he says, referring to a pan that called the movie “pretentious and interminable.”

One trashing aside, the evidence that Lowery’s career has reached a new level is unavoidable. For months now, scripts and story ideas are being pitched his way: might he be interested in directing a new take on Highlander? What about a remake of The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas? At present, Lowery’s cell phone has gone dead, forcing people to reach out to Halbrooks in the hopes that they might then get to Lowery. An executive at Sony Pictures Classics is particularly eager to talk to Lowery because his company is interested in distributing Ain’t Them Bodies Saints.

At the same time, though, there is countervailing evidence that, at the end of the day, these are still just a bunch of scrappy young hopefuls from Texas. At one point, Halbrooks calls his grandmother, who is in the hospital, and encourages her to look at photos from the Saints premiere online. Waiting for them in Salt Lake City is Lowery’s wife, Augustine Frizzell, and her stepdaughter, Atheena; Johnston’s wife, Amy McNutt (with whom he owns the Fort Worth vegan restaurant Spiral Diner and its Dallas counterpart); and Curtis Heath, a schoolteacher who composed some of the songs in Ain’t Them Bodies Saints. The whole gang is going to have dinner at a local vegan restaurant while the movie screens.

To that end, Lowery tends to resist any categorization of himself as some sort of savior of Dallas filmmaking. For one thing, he’s adamant that the conversation be framed in terms of a “Texas scene”—one that includes Dallas and Austin and all points between. One where filmmakers from one city might work on projects being made in another. But he acknowledges that working mostly outside of the indie hothouse atmosphere of Austin—in a city where filmmaking remains something of a novelty—has been valuable. He can also recognize the hopes that some members of the Dallas artistic community have placed in him.

“When Bottle Rocket came out, I was 13 or 14. It was so awesome to see these guys from Dallas were making something that was nationally recognized,” he says. “I got a job as a projectionist, because I knew that’s what Owen Wilson had done. If our film does well and people go see it and like it, I hope it inspires someone else in Dallas who is in film school—or not in film school. I hope it urges them to not go the easy route.”

Lowery is not sure, given the demands of the movie industry and his desire to do higher-budgeted work, if making Dallas a permanent base—the way Rodriguez and Linklater have made Austin—is even feasible. But he’d certainly like to try.

“I would love to be able to wake up in my own bed in the morning and then go to the set,” he says.

Traffic finally unknots, and the team begins making up for lost time. They make it to the Rose Wagner Performing Arts Center with about five minutes to spare. A volunteer tells them that every seat is filled and that people began lining up for standby tickets more than three hours ago. The movie plays arguably even better with this crowd, which is composed mostly of everyday movie buffs, than it did in industry-heavy Park City.

At the end of the film, Lowery is inundated with well-wishers eager to shake his hand and offer their effusive praise. He’s in the same spot that the likes of David O. Russell (Silver Linings Playbook), Darren Aronofsky (Black Swan), and Christopher Nolan (Inception) were 10 or 15 years ago, when they had their Sundance breakthroughs. You can imagine it won’t be much longer before a phalanx of handlers and publicists makes it impossible for any mere mortal moviegoer to get near him.

For now, he talks to everyone who wants to talk to him, and at one point, even gives his email address to two locals who would like to stay in touch.

•••

This is how quickly it can all change. This is why—even though he has been working to get here for nearly 15 years—a lot of folks are going to assume David Lowery is an overnight success.

On January 25, five days after its premiere, IFC Films acquired U.S. rights to Lowery’s film, in a deal reported to be worth just over $1 million.

A few weeks later, Lowery was in Los Angeles for the requisite post-festival “taking of meetings.” Then, in March, came word that he and Halbrooks had signed to write (but not direct) a reboot of 1976’s much-maligned live action-animation hybrid Pete’s Dragon.

In April, news broke that Lowery had also signed to write and direct The Old Man and the Gun, based on a New Yorker article by David Grann about a septuagenarian bank robber, with Robert Redford attached to star in and produce the film.

At first blush, the Pete’s Dragon announcement seemed strange—the edgy indie auteur going to work for the most family-friendly of all Hollywood studios. (Lowery acknowledged as much, posting just before the news broke in March on his Twitter feed: “I imagine a lot of people are about to be very confused.”) But throughout our conversations in Park City, Lowery said that if he could find the right Hollywood project among the countless ideas being pitched his way, he wouldn’t turn up his nose at it.

“We thought we could use that construct of boy and his dragon to explore themes that have been prevalent in everything I’ve done,” he tells me during a phone conversation in June. He was calling from the Louisville’s Flyover Film Festival (where he had just screened Ain’t Them Bodies Saints), on his way to Los Angeles (where he would participate in a press junket for the film).

“This didn’t happen overnight,” Halbrooks says. “It does feel organic, taking these baby steps along the way. But there were times when David and I first met where we had to rough it, doing things completely alone, literally not having money to pay bills. There were years where David didn’t have a driver’s license and we were sharing rides and cars.”

The Old Man and the Gun is perhaps the more predictable choice—the sort of prestige project that, if it were to be made, could easily launch Lowery into the front ranks of Hollywood filmmakers. Yet Lowery is also acutely aware of the fact that Sundance fame can be fleeting. Projects can get caught in development hell. Studios and agents quickly lose interest if a follow-up isn’t forthcoming—or if it fails to live up to the promise of the breakthrough. (To wit: Tony Bui won the festival’s top prize in 1999 with Three Seasons—and hasn’t directed a film since.)

“It’s good to have multiple things in the fire right now,” Lowery says. “But at the same time, I really wished that I could have snuck up and surprised people with the next movie. Because if these movies don’t happen, people will start to wonder and ask questions about what I’m doing.”

•••

The other Dallas-based efforts at Sundance this year fared nicely, too: the much-smaller-scaled Pit Stop (which is still searching for a distributor) earned favorable comparisons to the indie hit Weekend from a few years ago. As many people as it left mystified, Carruth’s Upstream Color earned its writer-director enthusiastic attention from the likes of Time, Wired, and the New Yorker. (Carruth self-distributed the film, beginning in April, though it only grossed about $450,000. It’s now available on DVD and streaming on Netflix.)

Yet even if an artistic film community in Dallas has finally been established, an unanswered question remains: can the city hold on to its filmmakers? Carruth recently moved out of his rental house in Plano and now divides his time between New York and Los Angeles. Although he still visits Dallas often, Yen Tan has lived in Austin for the last few years. And, indeed, the guys behind Ain’t Them Bodies Saints would be the first to tell you that their one lingering disappointment is that a film meant to be shot in Texas was mostly filmed in Louisiana, because Texas doesn’t offer competitive tax incentives to shoot films within its borders. (In the just-passed 2014-15 budget, the Legislature boosted incentive funding to $35 million over two years, but the incentives still lag behind those offered by many other states, such as Georgia and Louisiana.)

“Every city needs a David Lowery—a staple that people can look up to, like a Richard Linklater,” says James Faust, artistic director of the Dallas International Film Festival. “Maybe this is the wake-up call the Legislature needs to build a better incentive program. Because this was a Texas story by a Texas director, and it still ended up shooting in Louisiana.”

Whether Lowery can become that Linklater-like figure—someone who can move easily between personal projects like Before Midnight and studio films like School of Rock, and who does it all from his home base of Texas—is yet to be seen.

The first test will come this month, when IFC Films opens Ain’t Them Bodies Saints in the top 40 markets across the country. The company is placing a big bet on Lowery and the film; it’s one of the largest releases ever for IFC. Meanwhile, a first draft of the Pete’s Dragon screenplay has already been submitted, and—as of June—Lowery and Halbrooks were waiting from notes from their producers. Lowery says he has also completed about 45 pages of the script for The Old Man and the Gun, which he hopes to have finished by the fall.

So is he the most important filmmaker to ever emerge out of North Texas?

“I definitely don’t want to be perceived as The Second Coming of anything, because I’m not,” he says. “This could all go away in a second. I hope it doesn’t go away. I want to be able to make bigger and better movies, but if I need to make another $12,000 movie like St. Nick next year, I’m prepared for that, too.”

If there’s perhaps one thing David Lowery still needs to work on, it’s developing a little bit of the Hollywood ego.