“I was in tears,” Lamont says. “I thought, If you cut me, I may never be able to have babies. And I was scared to death of surgery.”

Dr. Ku was licensed to perform surgery at several hospitals. So he told Lamont to tour a few facilities and let him know where he should operate. His office was near Baylor Medical Center at Frisco. Lamont and her husband stopped by the hospital on their way home.

“When I walked in, I felt like I was going to a spa. There was a roaring fireplace. They had little sandwiches out and 15 different types of teas,” Lamont says. “There was a concierge desk, and they brought me a bottle of water. Someone came up immediately to give a tour of the hospital.” After viewing the spacious rooms, Lamont made up her mind.

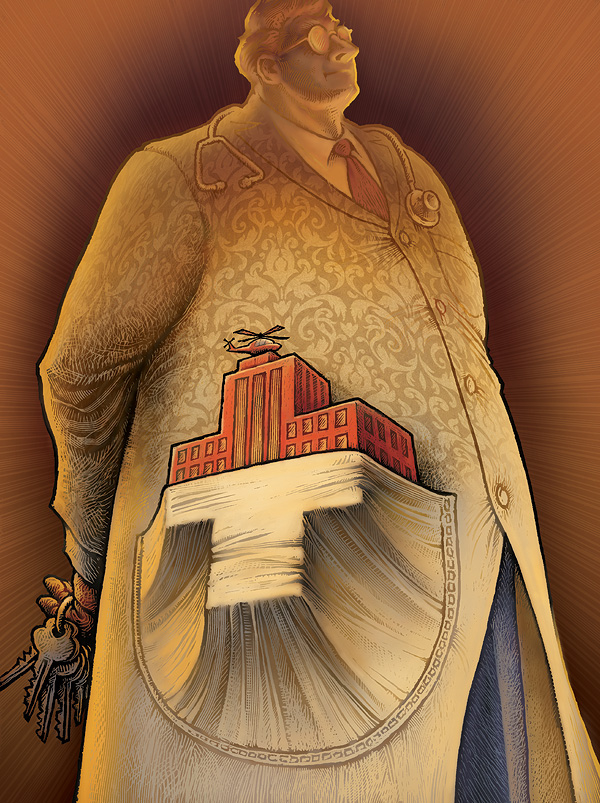

But, unbeknownst to her, she had chosen a somewhat controversial facility. She is one of 1.5 million people annually who decide to go to physician-owned hospitals. At Baylor Frisco, like other similar hospitals in the United States, the doctors have a direct financial interest in the hospital’s profits. This contrasts with other for-profit facilities that divvy up their earnings to shareholders or private owners.

Physician-owned facilities are being debated in Washington, D.C., and elsewhere. Opponents say doctors whose income is tied directly to a hospital’s profits are more likely to give advice and recommend procedures that pad the hospital’s bottom line rather than concern themselves strictly with their patients’ outcomes. Moreover, these hospitals can drive other not-for-profit hospitals in the area out of business by cutting prices and luring patients with amenities. President Barack Obama’s health care plan is making it much more difficult for physician-owned facilities to grow.

But as Baylor Frisco, which opened in 2002 at Frisco Medical Center, shows, physician-owned facilities are not only good for the doctors. Patients are receiving better and safer services if their caregivers have something financially invested in positive outcomes. Advocates say that physician-owned facilities are a better choice, and their competitive presence is weeding out the subpar hospitals.

Here are the facts: in Texas, 17 of the top 20 hospitals are physician-owned, according to a study by Consumer Reports that looked at things such as cleanliness, pain control, communication before and after surgery, and overall patient satisfaction. Physician-owned facilities ranked first in 20 states in the country, despite making up only 5 percent of the hospitals nationwide.

Baylor Frisco, in its own right, is one of the best. It ranks 11th in Texas on the Consumer Reports study. All but one of the facilities ahead of Baylor in the area are specialty hospitals, such as those that focus on heart surgery. Baylor Frisco is a full-service hospital and even has an emergency department. And Baylor stacks up better than every other non-specialty hospital in Collin County. According to the U.S. Health and Human Services Commission, Baylor Frisco received better marks than hospitals such as the Allen and Plano facilities of Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital in all 10 categories on a recent survey.

It helps that the hospital was founded by physicians who saw room for improvement. “We wanted a place where the patients weren’t just a hospital number or a medical number,” says Dr. Jimmy Laferney, an anesthesiologist who has practiced in Collin County since 1983 and is one of the founding doctors of Baylor Frisco.

Baylor offers several niceties. One is the steak and lobster dinners that delivery patients are offered before they check out. Patients can special-order their meals, too. Lamont didn’t feel like eating one day after her surgery, Dr. Ku remembers. “She liked chicken tenders,” he says. “I called chef Carl, and he made them.” Ku points out that on the day of our interview, he had steak, potatoes, and chicken and avocado soup for lunch.

But Baylor’s success isn’t just about a nice cafeteria. Unlike at many other for-profit facilities, doctors are on the board of directors. Some of them do have a financial interest, yes, but they also have patients in mind. “Physicians take a very active role in the management and have immediate decision-making power through the board of directors,” says Dr. Michael Russell, an orthopedic surgeon in Tyler and president of the trade group Physician Hospitals of America. “There is immediate feedback without going through the hierarchy of a large hospital.”

Because the doctors run the hospitals, there is often less red tape. They can organize procedures to help surgeries. For example, if a patient needs it, Baylor Frisco sends a kit to him or her before surgery with a sterile cloth to clean the affected area. This is just one additional safeguard to keep infection rates low.

Physician-owned facilities like Baylor Frisco also have a more organized approach to operating teams. They line up specific groups of nurses and technicians for each doctor. The staff can get accustomed to how each team member works. Russell says a day of surgeries at a traditional hospital might take him two hours longer than at a physician-owned facility. Surgeries are more efficient, surgeons are more rested, and the consistency leaves less room for error.

Ku echoes Russell’s experience. “At other hospitals, there could be a scrub tech in my room that typically works for orthopedics,” he says. “I could walk in, and the tech might say, ‘I don’t usually do this. I don’t know these instruments.’ But at Baylor, Dawn is my scrub tech. She is my girl.” Baylor Frisco has an infection rate of just 0.04 percent, far below the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention’s 2 percent optimal threshold.

Still, people take issue with physician-owned facilities. One problem is that health care, as a business, makes people uneasy—and it is more blatantly a business when doctors are direct owners. The people running physician-owned hospitals point out that every hospital thinks about its bottom line. And they, of course, are no exception. “We understand that good outcomes and satisfied patients will lead to financial success,” says Bill Keaton, Baylor Frisco’s CEO.

Not all patients get access to physician-owned facilities. Some insurance policies don’t cover the services at these hospitals. Russell says that in some cases, not-for-profit hospitals have lined up exclusive contracts with insurance companies so that patients are unable to go elsewhere in the area.

But physician-owned hospitals aren’t typically the ones helping poor people, either. Low-income patients often go to not-for-profit hospitals. So it might be harder for not-for-profits to stay in business when a fancy physician-owned facility in the area is taking all the paying customers. Obama’s health care bill is looking to make it more difficult for physician-owned hospitals to operate by restricting new doctor-owned facilities from participating in Medicare.

But independent researchers say that this is ultimately bad for the health care system. “These [not-for-profit] hospitals are almost always protected,” says Robert Moffit, a 20-year veteran at the Heritage Foundation, a conservative-leaning think tank in Washington, and deputy assistant secretary at the United States Department of Health and Human Services during the Reagan administration. “The uncompensated care costs are compensated for by the taxpayers,” Moffit says. “We have established a safety net to be sure these institutions don’t go under.”

Even Democrats oppose this aspect of Obama’s legislation. Texas Congresswoman Sheila Jackson Lee has been fighting hard to loosen the restrictions on physician-owned facilities since Obama’s health care bill first came across her desk.

“Opposition is nothing more than anticompetitive rent-seeking,” Moffit says. “They don’t want the competition, and, in my view, the reduction in competition is a bad thing for the health care community in general.”

As for Michelle Lamont, she says she feels fortunate to have had Baylor Frisco as an option. “I went through exceptional trauma, and they really helped me,” she says. It took her six months to fully recover from her surgery. But she still has her sights on motherhood.

Write to [email protected].